I recently found myself at Joann Fabrics five minutes before the store closed, desperately selecting supplies for a project that was, of course, best completed that night. My delay was self-inflicted, but it got me thinking about times when much larger projects have been strained by access to supplies.

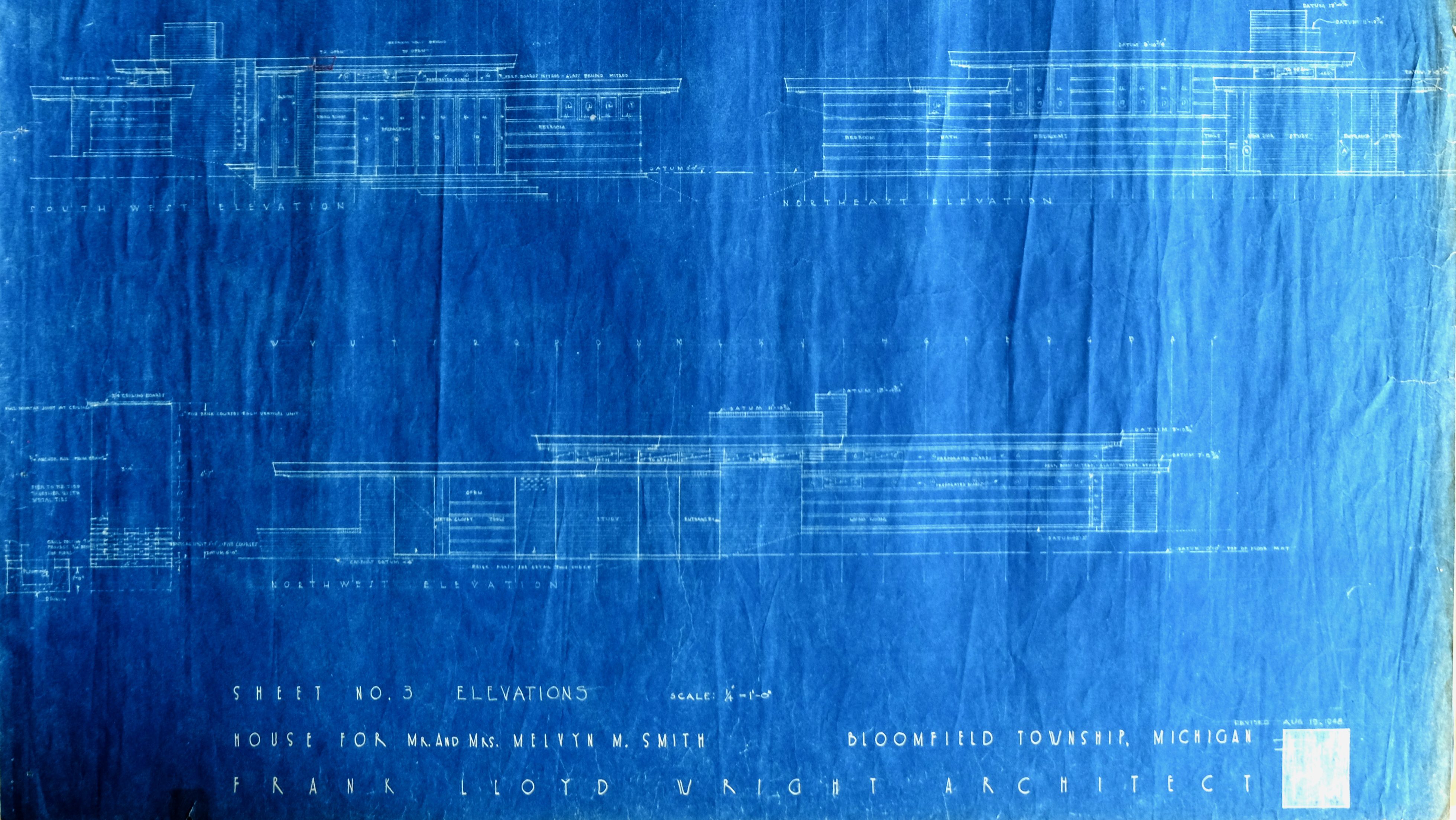

Specifically, both Eliel Saarinen and Frank Lloyd Wright created buildings with strong creative vision. Their architecture demanded specific, and sometimes hard to source, materials. Let’s look at two examples and decide if the headaches my favorite architects caused their suppliers and contractors/builders were worth the final product!

Example 1: Eliel Saarinen and Pewabic Pottery Tiles

When Eliel Saarinen specified thousands of hand-molded, hand-glazed, and hand-fired Pewabic Pottery tiles for use at Kingswood School for Girls, his contractor pushed back. Pewabic was less a tile factory than an artists’ workshop. As supplier of Kingswood’s industrially produced tile for bathrooms and basements, a concerned Mr. Burt of the Detroit Mantel and Tile Company wrote to the contractor, Charles Wermuth & Son:

We are doubtful as to [Pewabic Pottery] being able to manufacture the amount of tile as selected for this job. We raised this question during the course of selections but [Pewabic cofounder and artist] Mrs. Stratton advises that she will be able to produce this tile without any hold-up. We have advised her that any hold-up or delays caused from her material will be charged back to her.

We are writing you this letter merely as a protection against delays beyond our control.

Saarinen wasn’t wrong to select Pewabic Pottery for Kingswood—it’s stunning and perfect in every way—but Burt wasn’t wrong about issues of production. It does appear that delays in the tile making caused delays in construction, raising blood pressure on both ends of Woodward Avenue.

As the first day of classes at Kingswood drew nearer, truck drivers from Cranbrook made near-daily trips to the pottery for small batches of tiles. I imagine the kiln-fresh mini-masterpieces still warm to the touch!

Did the delay in tile delivery keep Kingswood from opening on time? No. An outbreak of polio in metro Detroit meant all schools were closed by state health officials. But Wermuth used the extra time to finish the building—all Pewabic tiles were well-set and grouted for classes to begin September 21, 1931.

Example 2: Frank Lloyd Wright and “The Wood Eternal”

In February 1949, Melvyn Maxwell Smith was ready to start building his long-awaited dream: a wood and brick Usonian house designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. With enough money squirreled away to begin construction, Smithy was ready to order materials. Including 14,000 linear feet of clear, old-growth, 16’ x 1’ x 2” boards of Tidewater Red Cypress wood.

Wright had built in Cypress since at least 1914, with his first all-Cypress design, the Wiley House, coming off the drafting board in 1932. The iconic Usonian houses of the 30s and 40s are mostly built of this swamp-grown, super strong, rot-resistant golden wood.

Cypress proved to be perfect for Wright’s organic architecture. And by 1949, Cypress was incredibly hard to find.

Smithy wrote to many different lumberyards with his needed material list. Those closest to the swamps where Cypress grows—lumberyards in South Carolina and Louisiana—were unable to furnish the volume of wood needed. Lumber yards in the Midwest simply stated they did not carry Cypress. Chicago-based Hilgard Lumber Company wrote, “We duly received your inquiry…on a carload of Tidewater Red Cypress (clear grade) but clear grade in this species is extremely scarce.”

In February 1949, Fleishel Lumber Company of St. Louis (who had been forwarded Smithy’s large request) agreed to fulfill the order. Smithy simply needed to let the yard know when he wanted the wood delivered. Or at least, that was the idea.

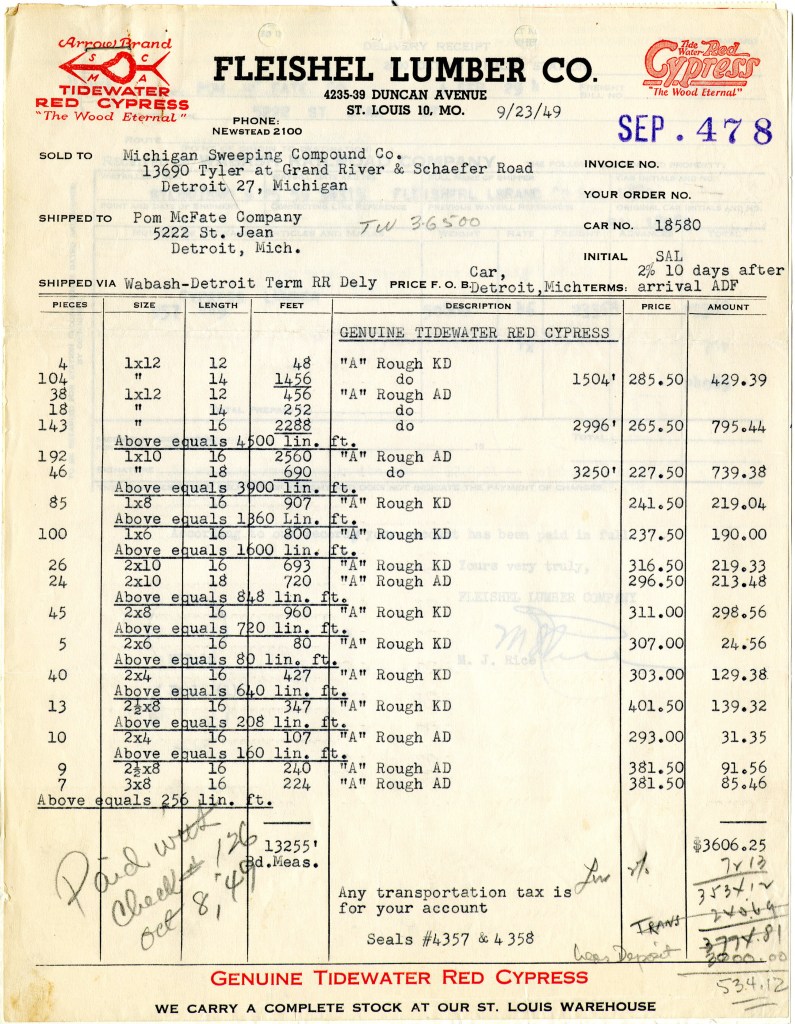

Every month, Smith wrote, called, or telegrammed Fleishel, asking for his order. And every month, the lumber yard replied: we don’t have it all, but we have some. As time ticked by and Smithy’s house waited to take shape, Fleishel offered up concessions. Instead of kiln dried, would Smithy accept natural dried Cypress? No. Recycled or swamp-preserved? No. Smaller boards, but more boards? No.

Smithy needed what Wright specified: long, wide boards. By August 9, 1949, things were looking up, even if Fleishel’s salesman sounds a bit annoyed:

…We are doing all we possibly can to accumulate all the stock to be put in the dry kiln.

As advised several times, we are having considerable trouble in accumulating the 1×12…We cannot, at this time, tell you exactly when shipment can be made. We regret very much this delay, but you must take into consideration this is quite a difficult list of items.

Smithy’s goal of having the lumber on hand during the Summer holiday, when he could be on-site every day, did not happen. His first day teaching his Cody High English class that year? September 5.

Finally, on September 23, 1949, Fleishel Lumber packed a railroad car full of 14,000 linear feet of clear, kiln-dried Cypress and sent it toward Bloomfield Hills. Just seven months and a few days after it was ordered.

About seven months later, Melvyn and Sara Smith had a Cypress house! When it was completed in May 1950, the Smith House became Frank Lloyd Wright’s last entirely Cypress-built project.

So, did being particular about materials pay off for Mr. Wright and Mr. Saarinen? I think the Smiths and thousands of Cranbrook students would agree: absolutely.

—Kevin Adkisson, Curator, Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research

Note: Oh, and if you want old-growth Cypress today? The current owner of the Frank Lloyd Wright Willey House, Steve Sikora, described the purchasing of Cypress wood in the 2010s as operating among “an assortment of hucksters, charlatans, and petty criminals, or in industry parlance, ‘wood brokers.’” Head on over to The Whirling Arrow blog to read a lot more about Cypress and Wright!

Discover more from Cranbrook Kitchen Sink

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.