It was the morning after New Year’s Day. No sooner had I reached my office and turned on my computer than I saw that I had just missed a call from long-time Cranbrook friend and Kingswood graduate, Jeanne Graham. Always eager to speak with Jeanne, I immediately returned her call. Jeanne, who had not even taken time to leave me a message, already was in the processing of dialing the Center’s archivists. She had a question and was eager for an answer.

Like Jeanne, one of the movies that I saw over the holidays (one of the best, I might add) was Green Book. Masterly cast with Mahershala Ali as the legendary African-American classical and jazz pianist Don Shirley and Viggo Mortensen as the Italian-American bouncer-cum-driver and bodyguard “Tony Lip” Vallelonga, the film tells the story of a road trip (a concert tour) through the Jim Crow South of the early 1960s and the unlikely friendship that develops along the way. While I was watching the movie, Cranbrook was the furthest thing from mind; while Jeanne was watching the movie, she could not get Cranbrook out of her mind. “Was it my imagination or did I attend a concert by Don Shirley in Kingswood Auditorium while I was a student at Cranbrook in the 1950s?” Jeanne asked.

Admittedly stumped, I did what any good director would do—I consulted my knowledgeable staff. Within minutes, tantalizing facts were speeding their way to me from Associate Archivist Laura MacNewman: articles in the Clarion and the Crane, Kingswood’s and Cranbrook’s student newspapers; a concert announcement in the Birmingham Eccentric; links to nineteen Kingswood negatives; and references to thirteen letters sent between Shirley and his agents and Henry Scripps Booth, the youngest son of Cranbrook’s founders. Finally, Laura calmly announced that she had found black and white photographs of Shirley swimming and riding a bike at Henry’s and his wife Carolyn’s home near Cranbrook, Thornlea. I, meanwhile, yelled out in excitement!

Who knew? Well actually, there are a few people that did know. Before I could even begin to sift through the materials in Cranbrook Archives, I received a call from Carolyn Scripps, Henry and Carolyn Booth’s granddaughter. Carolyn also had seen Green Book and wanted to make sure that I knew about the story of her progressive grandfather and Shirley.

Scene One. Shirley did, in fact, perform in Kingswood Auditorium on Wednesday, March 2, 1955 (and yes, it was while Jeanne Graham was a student). Shirley, who was twenty-seven years old at the time, was accompanied by bassist Richard Davis. They performed nine songs that evening, many of which the two musicians recorded on Shirley’s 1955 album Tonal Expressions, including one of my favorites, “No Two People Have Ever Been So in Love.” What does a rendition by Shirley of a popular song like “No Two People” sound like? In the words of Henry Booth: “While the concert was labeled ‘Jazz,’ the music was a subtle rendering of the contemporary, having a classical quality which should appeal to the devotees of classical music—that is if they will condescend to listen.” Five days after this classically inspired, popular jazz concert, Henry wrote his first letter to Shirley (at least the first one that survives in Cranbrook Archives). With regards from his wife Carolyn and their daughter Melinda (Carolyn Scripps’s aunt), Henry invited the pianist to consider a second performance at Cranbrook sponsored by the nascent Cranbrook Music Guild.

Scene Two. While it took numerous letters from Henry to both Shirley and his agent—and some convincing of the Music Guild members who Henry described to Shirley as not very “’Jazz’ minded”—the pianist and bassist returned to Cranbrook in December. Thanks to clippings from the Birmingham Eccentric and the Crane, we know the concert took place on Saturday, December 3, 1955, and, like the first concert, it took place at Kingswood. And thanks to a page in the Thornlea Guest Book, now in the collection of Jeffrey Booth (Henry and Carolyn’s grandson), we also know that Henry and Carolyn hosted an Afterglow for the musicians that evening in their home on Cranbrook Road.

Scene Three. Henry Booth was a documentarian. Included in the Henry Scripps Booth and Carolyn Farr Booth Papers, which are preserved—and accessible—in the Cranbrook Archives, are a series of photo albums that chronicle and illustrate Henry’s and Carolyn’s lives. The 1956 album includes seven black and white photographs of Shirley. While they were processed in July, another entry in the Thornlea Guest Book more precisely places both Shirley and Richard Davis at Cranbrook on June 20, 1956. Three of the photographs were taken by Henry at a night club, presumably Baker’s Keyboard Lounge in Detroit where the Don Shirley Duo performed no less than twelve times that June. One shows Shirley on stage, while the other two show Carolyn and Melinda Booth in the audience, including a photograph of Carolyn and Shirley sitting together at a table. The other four show Shirley relaxing at Thornlea—sitting in a wicker chair, swimming in the pool, riding a bike in the courtyard, and posing with the Booth’s youngest child, Melinda’s sister Martha (Carolyn Scripps’s mother). Henry, ever the Cranbrook publicist, dutifully followed up the visit by sending to Shirley “a selection of Cranbrook catalogs and booklets.”

Scene Four. There is where it gets interesting. While Green Book has Shirley and Tony Vallelonga departing from Shirley’s Carnegie Hall apartment and beginning their 1962 concert tour with a stop in Pittsburgh before immediately heading south, the actual route also brought them to Detroit. During the road trip, Vallelonga wrote letters to his wife Dolores. In an excerpt from one of the letters, published on Cinemabuzz.com, Vallelonga wrote:

Dr. Shirley decided to stop off in Detroit for a day to visit some people he knows, you remember I told you he knows people wherever he goes and he knows all big people (millionaires). We went over some guy’s house, I’m sorry I meant a mansion, it was really a castle. His name was Henry Booth, he lives in a place called Mich Hills, it’s like Riverdale Yonkers, but the place makes Riverdale look like the Bowery. Dolores, I never saw such beautiful and fabulous homes in all my life.

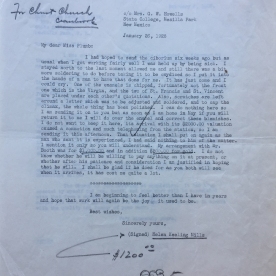

I’m guessing this visit to “Mich Hills” took place in April 1962. In a letter dated April 25, Henry wrote to Shirley, referencing a visit that took place “a week or so ago.” Eager for another concert at Cranbrook, Henry proposes that the Music Guild bring the Don Shirley Trio to Cranbrook that summer for a week of concerts in the Greek Theatre. But he also references “Carol’s original idea” (Henry referred to Carolyn as Carol): she wanted Shirley to be their guest at Thornlea on August 11, which would have been Henry’s sixty-fifth birthday. In his letter Henry was emphatic: “This is a definite date — put it down please!” In the only letter in the Archives from Shirley to Booth, Shirley references their telephone conversation and offers a very business-like reply to the concert requests: “Although our usual contract fee for an evening concert by the Trio is $2500.00, we would be delighted, for various reasons, to play at Cranbrook during the evening of 12 August 1962 for a special all-inclusive fee of $1250.00.” Alas, even the comprehensive records of Cranbrook Archives contain no evidence that the summer concerts or birthday party guest appearance transpired.

Letter from Don Shirley to Henry Booth, Summer 1962. Collection of Cranbrook Archives, Henry Scripps Booth and Carolyn Farr Booth Papers (Box 40: Folder 9).

Final Scene. In April 1986, as Henry Booth approached his eighty-ninth birthday (he would live to be ninety), Henry reached out to Shirley one more time. Reminiscing about the first concerts in Kingswood Auditorium, one of which Jeanne Graham attended, Henry wrote hopefully about one more concert:

I hope a concert by you can be arranged for next fall or winter, although a summer concert in Cranbrook’s Greek Theatre would be a fine location except for having a good, well-tuned piano at your disposal rather than rain or a shower! Will you put me in touch with your agent? Please do! Meanwhile a big hug for Don Shirley.

The trail in the Archives ends with Shirley sending Henry a flyer of his upcoming concert in Carnegie Hall (where Shirley still lived in an apartment). At the very bottom the pianist simply drew an arrow pointing to the contact for his agent noting, “It’s all here.”

It is, indeed, all preserved here in the Cranbrook Archives. Because there will always be a Cranbrook connection that needs to be researched and a Cranbrook story that needs to be shared.

– Gregory Wittkopp, Director

Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research