This week marks the 250th anniversary of the birth of British artist Joseph Mallord William Turner. Born in 1775, by the time of his death in 1851 Turner had upended all the conventions of landscape painting.

Having won critical acclaim as a young artist, in his later years, Turner pushed the limits of his art form beyond popular comprehension. His late work was dismissed in his lifetime as slapdash and unfinished, but was praised in the twentieth century for its free interpretation of light and color, verging on abstraction. Turner bequeathed three hundred paintings and thousands of prints and watercolors to the British nation in his will; today, works by Turner hang in dedicated rooms in both the National Gallery in London and Tate Britain, as well as in art museums around the world.

Cranbrook has one work by Turner in its collection, a watercolor view of Lambeth Palace and its surroundings.

Painted in 1790 when Turner was just fifteen years old, the watercolor is an alternate version of Turner’s first exhibited work at the Royal Academy of Art. The Royal Academy watercolor is now in the collection of the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields; the other watercolor is here at Cranbrook, part of the Cultural Properties Founders Collection that is stewarded by Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research.

George Booth purchased the watercolor in 1925 from Kennedy & Co., a large New York-based art gallery. George Booth would also purchase dozens of etchings from Kennedy & Co. to give to Cranbrook School, Kingswood School, and Cranbrook Academy of Art Library. Booth displayed the Turner in the original Cranbrook Museum, the precursor of both Cranbrook’s Art Museum and Institute of Science.

Lambeth Palace depicts a cluster of buildings on the north bank of the Thames, just south of Westminster Bridge. The slightly strained perspective on the angled sides of the buildings hints at the young Turner’s limited training at this stage of his career, while the wide expanse of cloudy sky in the picture, touched at the left with the pink of sunset, foreshadows the dramatic skyscapes that would characterize Turner’s mature paintings.

The site of Lambeth Palace has been the official London residence of the Archbishops of Canterbury since the 13th century. The square-towered, red brick building in the background of Turner’s painting is Morton’s Tower, added to Lambeth Palace during the Wars of the Roses. The small cottage and large white pub in the foreground have since been demolished, but the setting otherwise remains much as it was when Turner painted it.

Today, the Lambeth Palace complex is also home to the official archives of the Church of England, including early medieval illuminated gospels and a copy of the Gutenberg Bible, and to a Garden Museum, two institutions that George Booth, an enthusiastic gardener, book collector, and self-taught printer, would have probably admired.

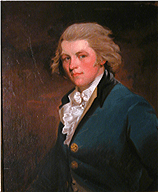

Now at Cranbrook House, Turner’s Lambeth Palace hangs near two works by his contemporaries, Sir Joshua Reynolds and George Romney. The three paintings, all purchased by George Booth, represent a turning point in the history of British art when the newly-established Royal Academy garnered unprecedented esteem for art as a profession.

The training offered at the Royal Academy to young artists such as Turner, and annual summer exhibitions where Turner competed with John Constable for popular acclaim, shaped the emerging school of modern British art. At the same time, the creation of the Royal Academy imposed an institutional authority on aspiring artists, restricting its students to a single ideal style and a narrow range of acceptable subjects.

Of the three British painters whose work George Booth collected (Sir Joshua Reynolds, George Romney, and J. M. W. Turner), Reynolds served as the first President of the Academy, Romney refused to join or exhibit there, and Turner taught, studied, and exhibited regularly, meeting sometimes with acclaim, sometimes with disgust, as his work gradually pushed the bounds of what was acceptable, in terms of subject matter and technique alike.

George Booth may well have had the complicated impact of the Royal Academy on British art in mind when establishing his own art academy here at Cranbrook. Certainly, his inclusion of a Turner in the community’s collection suggests that George Booth, at least, felt that Cranbrook students had something to learn from Turner’s life, his career, and his extraordinary artistic legacy – more widely celebrated now than he ever was in his own life.

— Mariam Hale, 2023-2025 Collections Fellow, Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research

Eds. Note: You can view Cranbrook’s Turner on guided tours of Cranbrook House through Cranbrook House & Gardens Auxiliary or on the Center’s Three Visions of Home tours.

Discover more from Cranbrook Kitchen Sink

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Mariam, love the info about this watercolor. I am always delighted to learn more about the items at Cranbrook House.

LikeLike