Any chance you have a trip planned to Europe this summer? If so, your itinerary really must include Stockholm. Not only is it a beautiful city—one of my favorites—but it also was home to one of Cranbrook’s most celebrated artists, Carl Milles. Long before he took up residence at Cranbrook, the Swedish sculptor started to plan and build his home and studio, Millesgården. Built high on a cliff overlooking Stockholm’s harbor, Millesgården now is a magical museum and sculpture park and the site of this year’s summer-long birthday party, The Sculptor Carl Milles at 150. Yes, if Carl Milles had lived to be the world’s oldest man, he would have turned 150 this Monday, June 23.

While anyone taking the time to read this blog no doubt has an image in mind of one of Milles’s works at Cranbrook (there are no fewer than 45 outdoors on our campus and another 52 in the Art Museum or other buildings), my guess is that the story of the twenty years he spent working in America are a little foggy (unless, of course, you attended our 2021 virtual fundraiser, A Global House Party at Cranbrook and Millesgården, and watched the film, Carl Milles: Beauty in Bronze, we produced for the occasion). As a refresher course, or even a primer, I thought I would take you on a journey, one that starts in America and ends, twenty-two years later, back in Sweden (and Italy, as the case may be).

Milles arrived in the United States for the first time in October 1929. With the stated purpose of attending the opening of his second group exhibition in New York City, he took advantage of the trip to sell work to collectors, negotiate a commission in Chicago for his Diana Fountain, present the concept for the monumental doors he would create for the Pennsylvania State Capitol, and meet with Tage Palm, the President of the Chicago-based Swedish Arts and Crafts Company who would become his business manager. Most important for this next chapter of his career, he also traveled by train to Michigan where he met with George Booth who asked him to teach at the art school he was building north of Detroit, Cranbrook Academy of Art.

George Booth and his wife Ellen Scripps Booth, as most Cranbrook Kitchen Sink blog readers know, were wealthy newspaper publishers and philanthropists. Although their flagship paper, the Detroit News, was based in Detroit, their home was in the countryside of Bloomfield Hills. By the late 1920s, they had begun to work with the Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen to transform their private estate into an educational community that eventually included an Episcopal church, boys and girls schools, an art academy and museum, and an institute of science (and, even later, a center for collections and research). Although the archival record is a little murky, Saarinen and Milles were at least acquaintances long before the sculptor met with his future patron at Cranbrook.

As Milles contemplated moving to Cranbrook to direct the Academy’s Sculpture Department, there was one small problem: he had no desire to teach. Two years and many conversations later, Booth and Milles came to an agreement: the sculptor would not need to “teach” but simply “mentor” students in his studio. (Not a bad deal!)

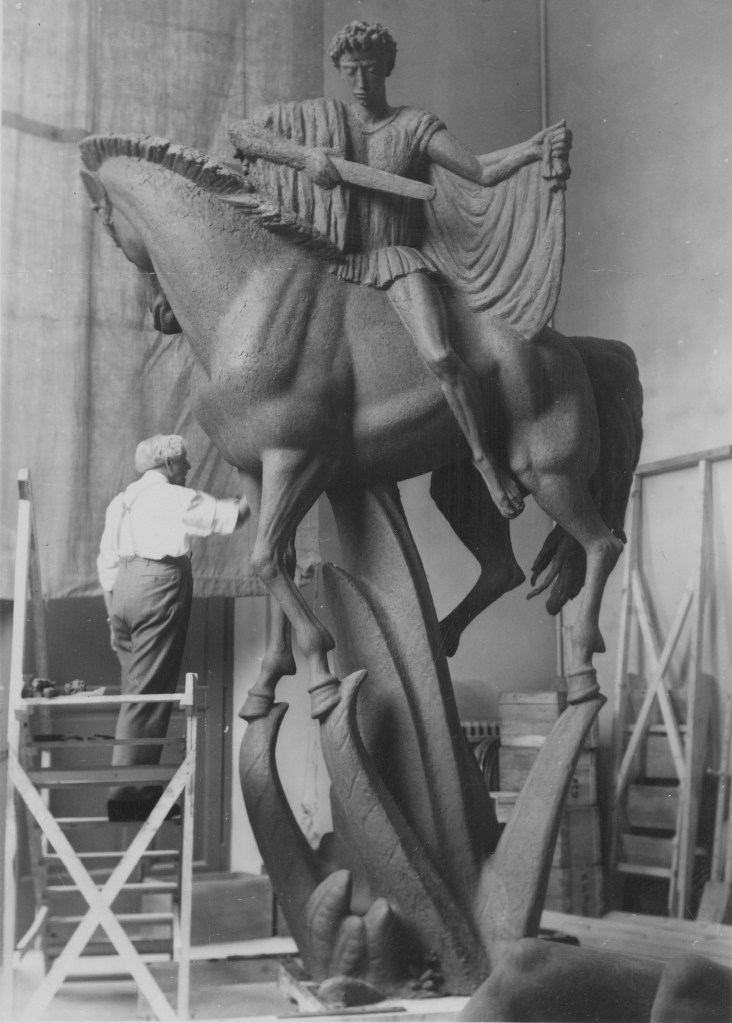

In January 1931, Carl and his wife Olga Milles arrived at Cranbrook where they lived for the next twenty years. Their home, where they displayed Milles’s collection of ancient sculpture, was designed by Saarinen, as were his three studios—including the grand thirty-foot-tall studio Milles used for his largest commissions such as the Orpheus Fountain for the National Concert Hall in Stockholm.

But Milles was not satisfied. He wanted to be surrounded by his sculpture just as he was at Millesgården. The four works Booth had acquired—including the only work Milles made at Cranbrook for Cranbrook, the playful Jonah Fountain—were not enough. In 1934, in the middle of the Great Depression, Booth agreed to pay Milles a princely sum—$120,000 and change—for sixty-three of his sculptures. This purchase not only included most of the works that had been part of a traveling exhibition that opened in St. Louis in 1931, but also casts of the eight figures from the Orpheus Fountain and his monumental Europa and the Bull from the fountain in Halmstad.

The decision, one that would come to define Cranbrook’s campus, was supported by Milles’s fellow Scandinavian and friend Eliel Saarinen, who Booth had named the President of Cranbrook Academy of Art in 1932. Indeed, there was a feeling of mutual respect between the architect and the sculptor, with Saarinen realizing that Milles’s work would enhance the buildings and Milles realizing that Saarinen’s architecture provided the perfect context.

Life was now good for Milles in America. Although he continued to spend much of the year in Stockholm or Rome, where he was a regular at the American Academy of Art, it was at Cranbrook where he worked on his largest commissions, including his three largest projects during the 1930s: the Peace Monument for the City Hall in St. Paul, Minnesota; the Doors of Agriculture and Industry for the capital in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania; and, most important for his visibility in America, the Meeting of the Waters Fountain in St. Louis, Missouri.

During World War II, new commissions all but stopped. 1940, nevertheless, proved to be an important year for Milles, beginning with the publication of an impressive book, Carl Milles: An Interpretation of His Work. Written by Meyric Rogers, curator at the Art Institute of Chicago and former director of the Saint Louis City Art Museum, the survey of Milles’s career presents him as a trailblazer, a sculptor whose work combines medieval and classic elements to create a fresh and original sculptural language. In addition to the book, a major exhibition of his work opened in Baltimore followed by two more in 1941, one in Boston and the other in Chicago where the Art Institute already had installed his Triton Fountain after the close of his traveling exhibition in 1931.

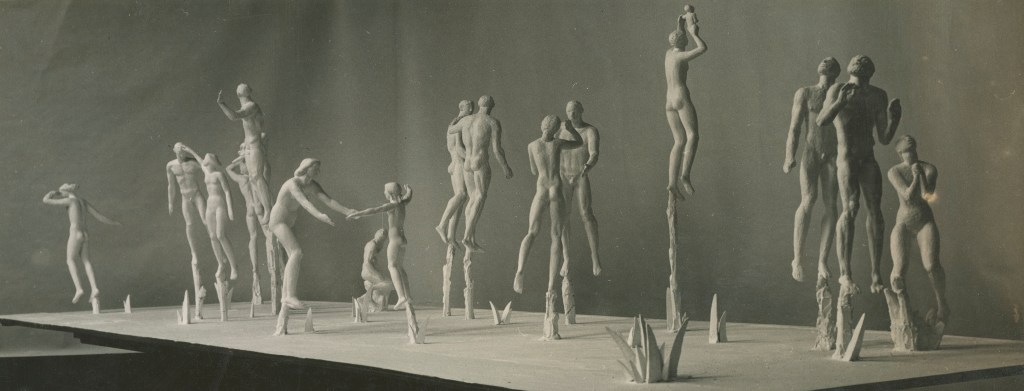

The project that dominated Milles’s thinking during his final decade in the United States was the Fountain of Faith near Washington, D.C. Commissioned in 1939 for the National Memorial Park, a private cemetery in Falls Church, Virginia, the commission started with a contract to create fourteen new sculptures representing reunion after death. By the time the fountain was dedicated in 1952, the commission included thirty-eight individual sculptures plus the placement of his Sunsinger elsewhere in the cemetery. Milles wanted this commission—the largest of his entire career—to be his “masterpiece,” the project that would define his career and perhaps, apropos the theme of the work, achieve for him immortality.

In 1951, Carl Milles left Cranbrook and returned to Europe to embark on the next and final chapter of his career, dividing his time between Millesgården and the American Academy in Rome. During these last four years of his life, he worked on three more American commissions: the Fountain of the Muses for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the St. Martin of Tours Fountain for Kansas City, and the Spirit of Transportation for the City of Detroit, all of which were installed after his death in 1955.

I could go on, and on. For the rest of the story, you really should make a trip to Millesgården—ideally before his birthday exhibition ends on September 28. I’ll simply close with one final image from the collection of Cranbrook Archives, a photograph taken by Harvey Croze at Carl Milles’s 70th birthday celebration in the Cranbrook Kingswood Dining Hall. In it you see Milles, with that famous “twinkle in his eye,” cutting his 70th birthday cake with a sculpting tool gifted by George and Ellen Booth’s granddaughter, Melinda ( just visible behind the flower arrangement), who waits for the first piece of cake.

Happy Birthday Carl!

—Gregory Wittkopp, Director, Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research

Discover more from Cranbrook Kitchen Sink

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.