Cranbrook Archives is excited to announce the acquisition of the Clifford B. West and Joy Griffin West Papers. Since the boxes arrived this past summer, I have been inventorying their contents in preparation for making them accessible to the public for research. Completing this work involves continually unravelling the many interesting facets of Clifford and Joy’s stories to be brought to light through the collection. Among many other things, are their experiences at Cranbrook in the mid-twentieth century.

Clifford and Joy attended the Academy of Art at the tail end of its golden age, meeting and marrying in 1941. At that time, Carl Milles, Eliel Saarinen, Loja Saarinen, and Eero Saarinen taught and worked on campus. Clifford earned his MFA in painting under Zoltan Sepeshy and Joy took ceramics classes from Maija Grotell. Fellow students included Lily Swann Saarinen and Harry Bertoia, among others.

Bertoia and West: Three Decades

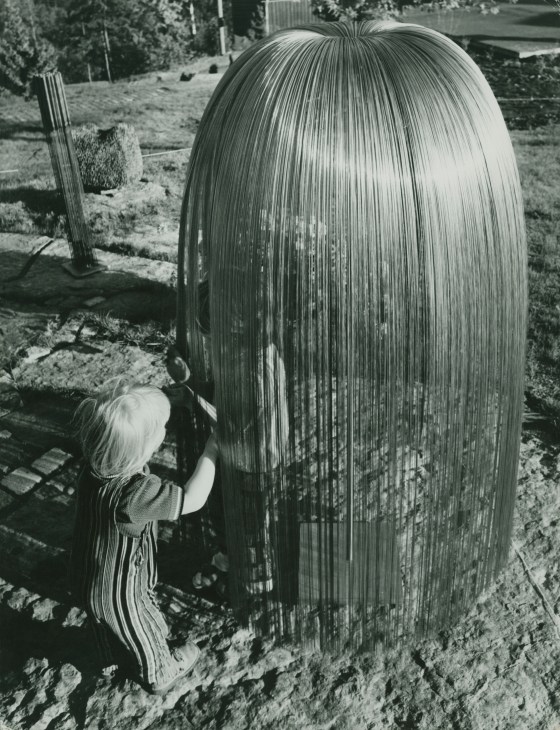

It was with Harry Bertoia, sculptor and designer, that Clifford enjoyed a lifelong friendship, serving as best man at his 1943 wedding to Brigitta Valentiner (fellow Academy student and daughter of Wilhelm Valentiner, Director of the Detroit Institute of Arts). While living in different parts of the country after graduation (or different countries all together), the two artists maintained close ties, both personally and professionally, evidenced by correspondence and other materials found in the Wests’ papers. Of particular note is the original 16mm film Clifford made in 1965, titled Harry Bertoia’s Sculpture, featuring a soundtrack by Bertoia.

Another fascinating connection is Clifford’s involvement with a few 1976-1977 exhibitions of Bertoia’s sculptures in Norway. Bertoia’s work, including his sound sculptures, had been introduced to the Norwegian art scene in the late 1960s through Bente Torjusen, an educator at the Munch Museum who assisted Clifford on his 1968 film about artist Edvard Munch and later became his third wife. An accomplished filmmaker and photographer by the late 1970s, Clifford photographed the Bertoia exhibitions and designed the accompanying catalogs. In true Cranbrook fashion, Clifford’s artistic talents were not limited to just one medium.

The exhibitions would be the last collaborations between Clifford West and Harry Bertoia, as Bertoia would succumb to lung cancer one year later. Fifty years on, Cranbrook Art Museum will celebrate Harry Bertoia in an upcoming exhibition, opening summer of 2027. Bertoia’s work was last featured at Cranbrook in the 2015 exhibition, Bent, Cast, and Forged: The Jewelry of Harry Bertoia, which marked the centennial of his birth and the first exhibition devoted to his jewelry designs (see the full catalog here).

I look forward to uncovering and sharing more about Clifford and Joy’s remarkable lives. Stay tuned!

—Deborah Rice, Head Archivist, Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research

Related announcement from the Harry Bertoia Foundation:

The Harry Bertoia Catalogue Raisonné is announcing a call for works from the Cranbrook community to more fully develop the publication’s coverage of the artist’s early jewelry practice, a currently under-described area of the artist’s oeuvre.

Present owners of jewelry believed to be by Bertoia are invited to contact the Harry Bertoia Foundation and Harry Bertoia Catalogue Raisonné by sending an email to: catalogue@harrybertoia.org, and submitting an owner questionnaire, available on our website. Museums, art galleries, and other institutions that are in possession of works by the artist are also invited to submit relevant data and photographic documentation. All information will be treated with discretion and held in strictest confidence.