Have you ever wondered what it would be like to cook in a kitchen designed by Frank Lloyd Wright? As the summer intern for the Center, I got a taste of the experience.

My name is Clare Catallo and I am a 2020 graduate of Cranbrook Schools and a rising senior at Kalamazoo College. I am a history major and I am hoping to have a career in museum curation. As a Schools student, I had the opportunity to tour Cranbrook House, Saarinen House, and Smith House and learn about the designers and art movements that are intertwined with the legacy of the campus. It sparked my interest in design history and material culture, and I am very grateful to have spent the past two summers interning with the Center.

Last year, I helped clean the exterior of the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Smith House, inventory the books in Melvyn and Sara Smith’s collection, and do genealogical research. This summer, I have been researching the histories of household objects and conducting object photography at Smith House, as well as assisting with the Cranbrook Horizons-Upward Bound Architecture elective course. In August, I assisted the Center team with preparations for “At Home with the Smiths,” an immersive evening program held at the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Smith House. Preparing for this event has brought my two summers here together as we work to emulate Melvyn and Sara Smith’s 1970s house parties.

The cookbooks found at Smith House provide a glimpse into the family’s lifestyle and the home cooking trends of the 1960s and 1970s. Many of the Smiths’ cookbooks present an image of a modern, working woman who has more to do with her time than spend hours in the kitchen. World War II had made families rearrange their menus and ideas about food, due to rationing and shortages which continued even through to the postwar years. Menus became less formal, and fewer families had maids to cook for them.

These national trends align with Frank Lloyd Wright’s kitchen design, meant to function as a utilitarian, servantless workspace. Combined with the growing numbers of women in the workplace in the 1960s and 1970s, the demand for quick and easy recipes rose. This trend is reflected in the Smiths’ cookbooks like the excellently-titled Dinner Against the Clock (Quick, Sumptuous Meals With the Look and Taste of Infinite Leisure), and The Keep it Short and Simple Cookbook, the latter of which is dedicated to “every homemaker,” whether “housewife, career girl, or bachelor”. These recipes use few ingredients, many of which are ready-made, require a small number of utensils, and demand little time.

Sara Smith was one of these busy women. She worked at Marsh Elementary, taught community theater, and had a vibrant social life. As we looked through the cookbooks, we noticed that most of the pages seem pretty new and fresh after almost sixty years. Perhaps the idea of the books was more comforting than the recipes themselves!

Even if Sara didn’t use them, there are plenty of interesting recipes to be seen in the cookbooks she collected and kept. The Blender Cookbook includes instructions for dishes like avocado soup, carrot custard, and a cottage-cheese-and-beet ring made of gelatin. Another pamphlet includes “king neptune delight,” containing milk, canned oysters, mushroom soup, canned shrimp, and green bell pepper. There are also drinks, including the eye-watering “dietini,” made with evaporated milk, pineapple juice, dextrose, corn oil and brewer’s yeast, and “meal in a minute,” which is orange juice blended with egg yolk and honey wheat germ.

Many of the cookbooks in the house were written to promote kitchen appliances that were growing in popularity in the postwar years, including Microwave Cooking Made Easy, The Blender Cookbook, and The Electric Knife Way to Better Cooking. New Casserole Cookery expresses how skilled young cooks can become “assisted by ingenious mechanisms.”

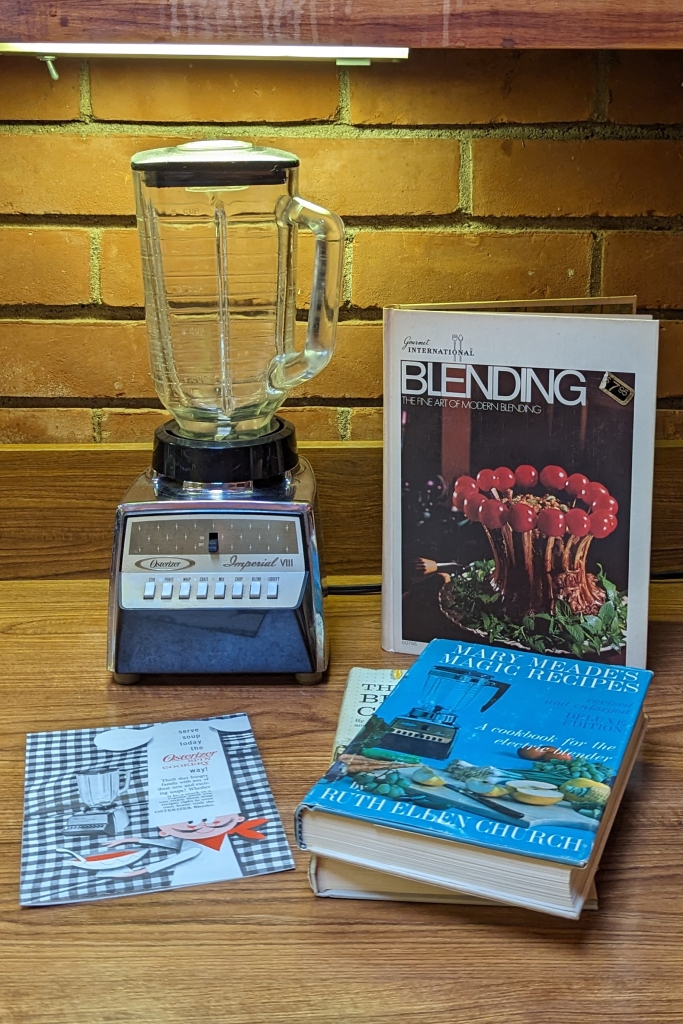

One of the gadgets that Melvyn and Sara used, perhaps to blend up their own King Neptune soup, was an 8-speed Osterizer Imperial VIII blender from the John Oster Manufacturing Company. They likely purchased it in the late 1960s for around $40, the equivalent of about $370 today.

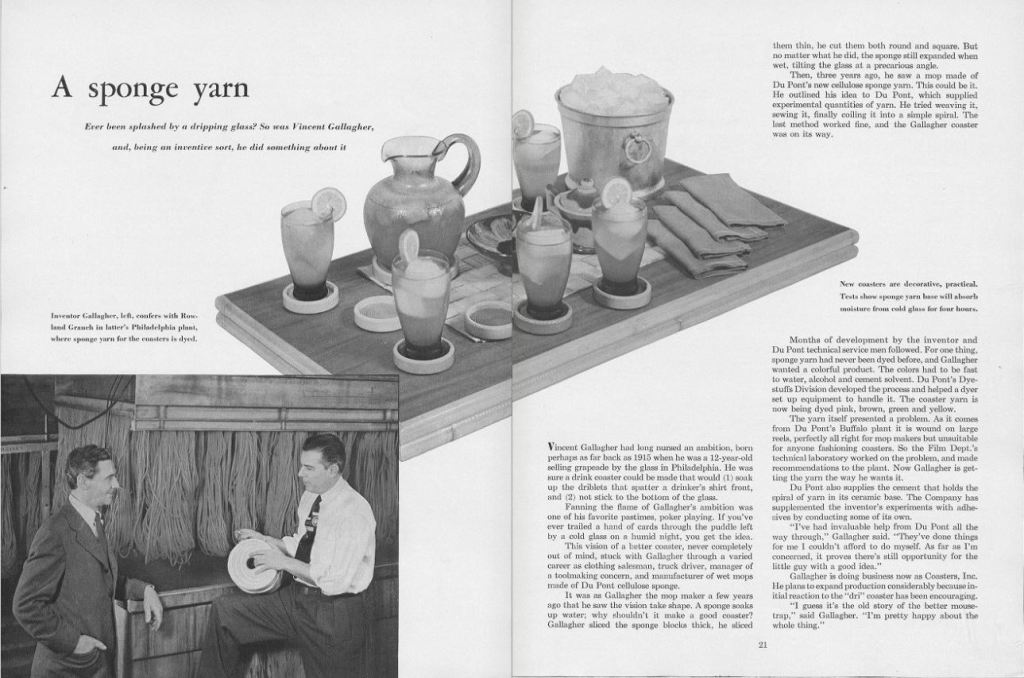

Whatever your choice of blended beverage, you could set your glass on one of the Smiths’ two sets of Design Trends “Dri-Coasters.” The protective coasters were invented by Vincent Gallagher, working as a wet mop manufacturer at the time. The mops were made of Du Pont cellulose sponge, and his logic was as follows: If a sponge can soak up water, why couldn’t it work in a coaster? However, no matter what he tried, the sponges continued to expand when wet. It was not until he saw Du Pont’s recent cellulose sponge yarn in 1949 that he found his material. Du Pont supplied yarn for his experiments, and he set to work weaving and sewing. In the end, he found his design in a simple spiral coil. In addition to the yarn, Du Pont also supplied the cement that holds the yarn in the base.

How would you wash up after a delicious glass of “dietini”? In the 1970s, Melvyn and Sara Smith installed a KitchenAid dishwasher. From close inspection, we believe that the Smiths re-used the beautiful maple plywood front of the original lower cabinet to clad the dishwasher, creating a more seamless look that integrated with the kitchen design. After their invention in the 1880s as a solution to chipped dishes, dishwashers had a slow crawl to becoming commonplace. KitchenAid portable dishwashers hit the market in 1935, soon followed by front-loading dishwashers and those with slide-out dish racks. In 1946, KitchenAid introduced pressurized dishwashers for residential use. After World War II, dishwashers increased greatly in popularity, a fitting addition to a servantless household.

Researching the objects at Smith House has shown me a lot of the depths and nuances within the postwar household. One of my favorite college classes so far was about postwar America, and this experience added a more human dimension to the books I have read about suburban life. I found the common theme of working women and decreasing time in the kitchen to be very interesting, and to receive this message in a Frank Lloyd Wright kitchen made it all the more fitting.

Do you have any memorable midcentury recipes, or appliances that have stood the test of time? Would you try a “dietini”? Let us know!

—Clare Catallo, Summer Intern, Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research

Editor’s note: “At Home with the Smiths” (September 6, 7, and 8, 2023) is an immersive evening experience where you can explore Smith House, its collections, and period-inspired food, drinks, activities, and apparel at your own pace. More information and tickets are on our website.

Discover more from Cranbrook Kitchen Sink

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Gee, that looks like my dishwasher!! Its a bit old…

LikeLike