Researching in the Archives before a big tour, I came across an interesting person whom I earmarked to come back and examine further. I already knew Loja Saarinen wove textiles for Frank Lloyd Wright, but Edna Vogel’s story of weaving for Wright intrigued me; it turned out there was a bit more to learn about Edna Vogel.

Edna Vogel in her weaving studio, July 1942. Joe Munroe, photographer. Courtesy of Cranbrook Archives.

Edna Vogel (1901-1953) grew up in St. Louis and studied at a teacher’s college and then Washington University in St. Louis. She wasn’t in love with teaching elementary school, but she did like making costumes, so in the early 1930s she went to New York to study dress design. Not finding the cloth she wanted in stores led her to discover an interest in weaving, and weaving led her to Cranbrook for summer courses in 1939.

Vogel studied at Cranbrook Academy of Art for four summers and two regular academic years, earning her MFA in May 1943. Like so many Academy students, Vogel bounced between disciplines, studying weaving with Marianne Strengell, ceramics with Maija Grotell, and working in the metals shop. She spent most of her time in the ceramics studio, with Grotell commenting in 1941 that Vogel had a “very fine understanding for color and form” and that “her technical research and discoveries are exceedingly valuable.”

Ceramics and place-mat by Edna Vogel, made as a student at Cranbrook. Detail of a photograph, June 12, 1941. Courtesy of Cranbrook Archives.

In the early 1940s, Vogel moved into the carriage house of Bloomfield Hills socialite Kate Thompson Bromley, who kept detailed diaries that include information on Vogel’s work and travels.

Vogel worked in the carriage house with two assistants between three looms (small, medium, and very large), she began weaving placemats, pillows, fabrics, and rugs. The largest rug Vogel wove was for architect Albert Kahn, in a Swedish style, and she wove others for Kahn’s family. She also wove the rugs for Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1941 Gregor Affleck House in Bloomfield Hills. Wright instructed Affleck to use long, strip-like rugs for his living room in order to leave much of the concrete floor exposed. Affleck, who may have met Vogel through Grotell or Bromley, commissioned rugs from her sometime in the early 1940s.

Thrilled with receiving the commission, Edna Vogel set off in her car towards Wisconsin and Wright’s estate, Taliesin. Approaching Taliesin, she became nervous that the famous Wright would not want to see her without an appointment. She ended up knocking on the wrong door of the house, introduced herself to an apprentice, and, to her surprise, being taken into a meeting with Wright. He seemed charmed—with both her and her ideas for the Affleck House rugs. He was so impressed by Vogel that he invited her to come and work at Taliesin as both weaver and ceramicist.

She stayed for a long weekend, but as remembered in Mrs. Bromley’s diaries, Vogel’s chief complaint with Wright’s work centered on his interest in providing functional architecture but not always functional furnishings. Wright did not, Bromley wrote, “aim to make a house and furniture one unit as at Cranbrook,” and so Vogel decided to return to Michigan and remain at the Academy. She completed the rugs for the Affleck House, and at a visit to the house later, Wright’s wife Olgivanna commented that the rugs were the “finest she had ever seen.”

Edna Vogel’s rugs for the Gregor Affleck House, c. 1941-45. Courtesy of Lawrence Technological University.

At the end of the 1940s, after exhibiting ceramics internationally and producing textiles for homes, Vogel moved to New York. She wanted a place to find new inspiration and focus on her weaving. In South Salem, about thirty-miles north of New York City, she bought a former school house with a first-floor residence and an open studio large enough for her 12-foot loom on the second floor. She produced rugs of various sizes that were noted for their painterly, subtle uses of color, and she maintained an extensive collection of yarns from around the world. Tragically, Vogel died of smoke inhalation in 1953 when a chimney fire spread to her yarn storage.

Rug by Edna Vogel, displayed at Cranbrook. Photograph, July 30, 1942. Courtesy of Cranbrook Archives.

We have just a few images of Edna Vogel’s works in our archives and I found only a handful more in periodicals in the Art Academy Library. If you know more about her, or where her work lives on, let us know in the comments or at center@cranbrook.edu.

– Kevin Adkisson, Collections Fellow, Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research

George G. Booth created the Still Room as a part of his office suites in 1918. It was as a place to take a noonday rest. In old English country houses, the Still Room was a place where medicines were prepared, herbs and flowers were infused in water or oils, and where home-brewed beers and wines were made. As Henry Scripps Booth recalled in another letter, “We started applying the term to the small room at the south end of the wing although Mr. Booth had no intention of making whiskey, beer or wine, but on using it as a quiet place for reading, conversation and taking undisturbed naps.”

George G. Booth created the Still Room as a part of his office suites in 1918. It was as a place to take a noonday rest. In old English country houses, the Still Room was a place where medicines were prepared, herbs and flowers were infused in water or oils, and where home-brewed beers and wines were made. As Henry Scripps Booth recalled in another letter, “We started applying the term to the small room at the south end of the wing although Mr. Booth had no intention of making whiskey, beer or wine, but on using it as a quiet place for reading, conversation and taking undisturbed naps.”

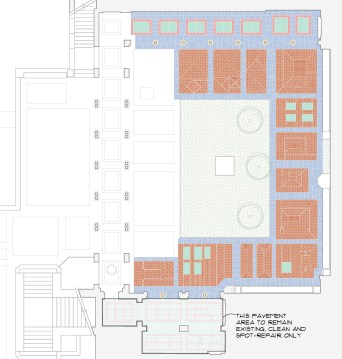

Once the demolition was complete, the contractor replaced the underground storm drain, which was originally clay piping, with new PVC piping. Clay piping is brittle and therefore susceptible to intruding tree roots which lead to leaks and clogs. The PVC piping will last much longer and minimize maintenance work. Once the PVC piping was installed, soil was filled in and compacted and the trenches were capped with concrete.

Once the demolition was complete, the contractor replaced the underground storm drain, which was originally clay piping, with new PVC piping. Clay piping is brittle and therefore susceptible to intruding tree roots which lead to leaks and clogs. The PVC piping will last much longer and minimize maintenance work. Once the PVC piping was installed, soil was filled in and compacted and the trenches were capped with concrete.  The next activity was demolishing the concrete bridge. All the existing limestone newel posts and railings were in good condition, so they were set aside to be reinstalled. The masonry wall, below the bridge, was also disassembled because many of the bricks were extremely fragile and showed

The next activity was demolishing the concrete bridge. All the existing limestone newel posts and railings were in good condition, so they were set aside to be reinstalled. The masonry wall, below the bridge, was also disassembled because many of the bricks were extremely fragile and showed  After a summer of careful work, the masonry wall and arches have been rebuilt to their original beauty.

After a summer of careful work, the masonry wall and arches have been rebuilt to their original beauty.  The concrete bridge has been layered with waterproofing, reinforcing, and heating pipes, and is ready to be poured back with concrete. The flat paving areas are being prepared for their final layer of brick and stone.

The concrete bridge has been layered with waterproofing, reinforcing, and heating pipes, and is ready to be poured back with concrete. The flat paving areas are being prepared for their final layer of brick and stone.  Look forward to a final update here on the Blog once the project is complete! As always, many thanks to the contractors who are working hard on this beautiful restoration.

Look forward to a final update here on the Blog once the project is complete! As always, many thanks to the contractors who are working hard on this beautiful restoration.