On this, the last day of summer, I thought we’d look back at the Center’s second-annual Architecture Elective for the Horizons-Upward Bound Summer Component. It was a real highlight of my summer!

A grant from the Society for Architecture Historians enabled Nina Blomfield, the Center’s Collection Fellow, and me to co-teach the six-week elective. Each Monday and Wednesday morning from June 28 to August 2, we met in Gordon Hall of Science at Cranbrook with fifteen enthusiastic HUB students, grades 9 through 12. While we started most mornings in the classroom with our textbook or a slideshow of images, the real excitement came on class trips.

I mean, what better way to learn about excellent architecture than to study the buildings of Cranbrook?

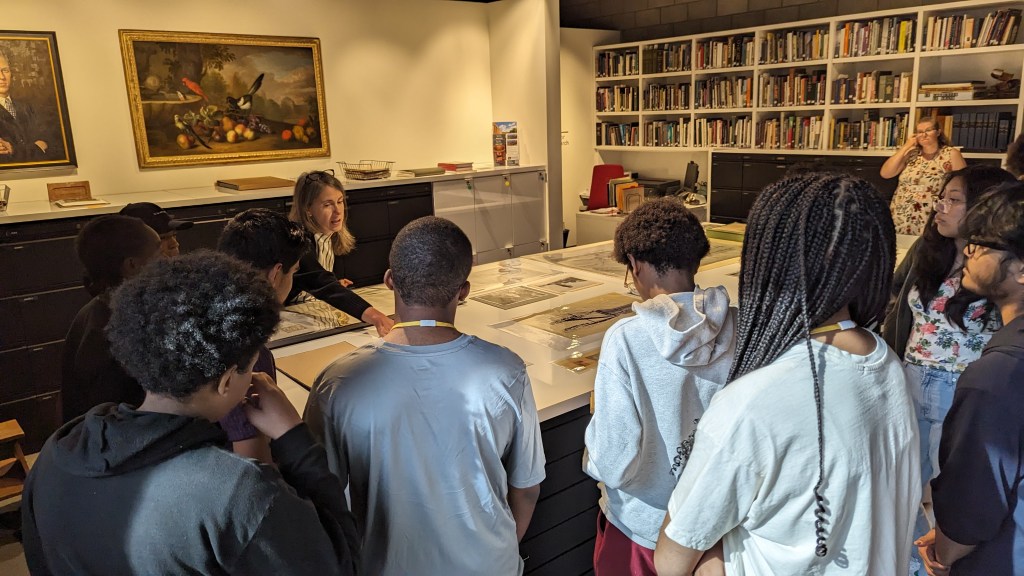

To orient ourselves, we started with a morning spent in Cranbrook Archives, studying original sketches, renderings, blueprints, photographs, and even fundraising literature about Cranbrook’s many architectural treasures. We saw the great diversity of how our buildings were imagined, represented, and constructed, and how an architect moves from a loose, gestural sketch to formal construction documents that communicate complex structural systems.

Then, we spent a class period each at Cranbrook House, Saarinen House, and the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Smith House. In each location, students carried their sketchbooks and made notes and drawings about the architecture. I was especially impressed at the students’ analytical skills. In fact, while I usually love talking about the nitty-gritty specifics of Saarinen House, I found myself sitting much more quietly, asking students questions about what they noticed, liked, or disliked in each room. Listening to their observations and conversation helped me see each space anew.

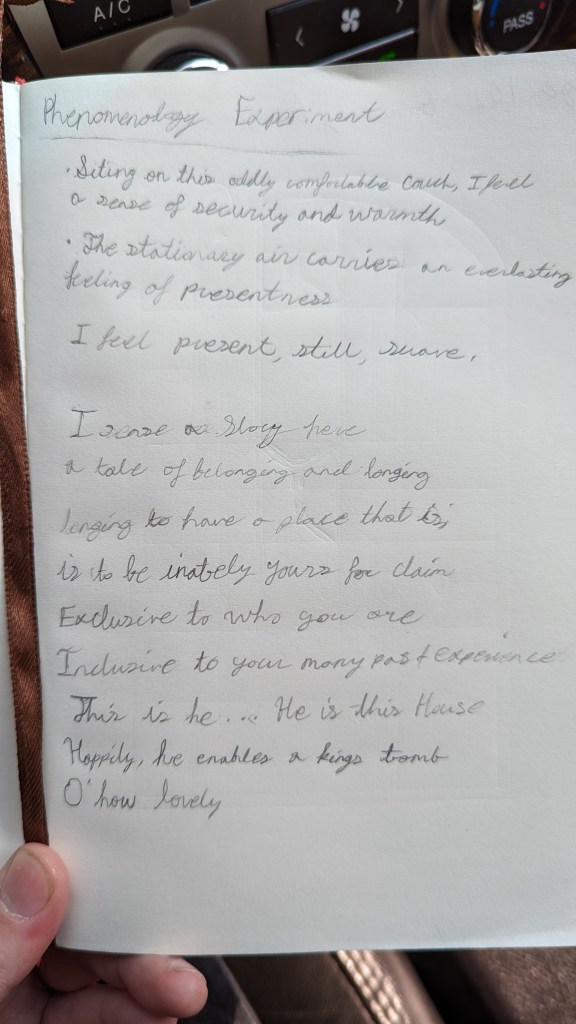

At Smith House, Nina led a phenomenology exercise, where, instead of telling the students the story of Frank Lloyd Wright and the Smiths, she simply asked each student to find a spot in the house to sit in quietly. Then, they wrote or sketched what they observed and sensed. Having such a tactile experience with the architecture and nature proved to be more memorable than a conventional tour.

Continue reading