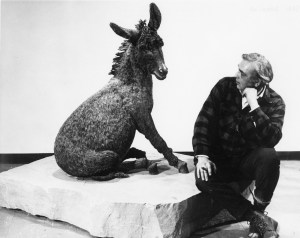

What would you want for your 75th birthday? If you were painter Robert Hopkin, it would be an artists’ club named in your honor. The Hopkin Club, formed in 1907, had no rules, officers, or dues. The members wanted to get together occasionally, to talk about art or host artists visiting Detroit. Hopkin passed away in 1909, but the club continued. In 1913, The Hopkin Club established by-laws and was renamed the Scarab Club–the name it continues under today.

But who was the man the club was originally named after?

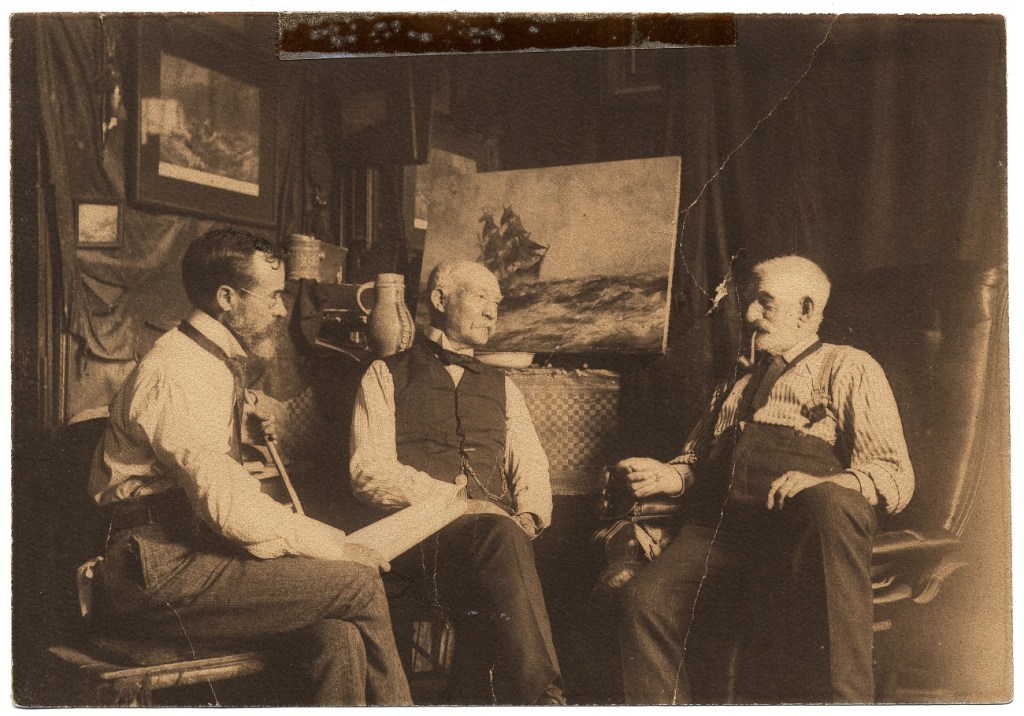

Robert Hopkin was a maritime/marine artist born in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1832. He learned to paint and draw from his father. The family emigrated to Detroit in 1842. His grandfather was a sea captain which drew Hopkin to work on the wharves in Detroit and inspired his art. Though chiefly known as a painter of marine scenes and seascapes, Hopkin made frequent trips throughout the American west from 1860 to 1885, painting murals for public buildings and drop curtains and scenery for theaters, including the Tabor Grand Opera House in Denver.

In the latter half of the 19th century, Hopkins was considered the dean of Detroit artists; he decorated the interior (as well as the stage curtain) for the original Detroit Opera House (1868), painted murals in Detroit’s Fort Street Presbyterian and Ste. Anne’s churches, as well as the Cotton Exchange in New Orleans (1883). By April 1900, the Detroit Free Press wrote, “Many of the art lovers of this city possess one or more of [Hopkin’s] splendid marines, and they have been reproduced and published until everyone is familiar with his work.”

When Mr. Robert Hopkin’s Collection of Paintings opened at the Detroit Museum of Art in May 1901, “There was a large attendance of art-loving Detroiters” (Detroit Free Press, May 16, 1901).

George and Ellen Booth were no exception. Art lovers with many Detroit-based and self-taught artists in their growing collection, the first inventory of Cranbrook House in 1914 lists two Hopkin “Marine” paintings. The Booths gifted the larger of the two paintings to their daughter Grace Ellen Booth and her husband Harold L. Wallace. The painting returned to Cranbrook House about 1955, when Grace Booth Wallace’s collection was donated to the Cranbrook Foundation.

The Detroit Historical Society has a copy of the Souvenir Catalogue of Mr. Robert Hopkin’s Collection of Paintings in its collection. The 85 exhibited paintings are listed, with several black and white images of them. “Price List” is written on the cover, and notes have been made indicating which have been sold and who purchased them. (Sadly, the name “Booth” does not appear.)

Another art-loving Detroiter was Merton E. Farr president of the American Shipbuilding Company and owner of a number of freighters on the Great Lakes. His daughter, Carolyn, married George and Ellen Booth’s youngest son, Henry.

In 1927, Farr gifted the couple a Hopkin “Marine.” The painting hung in Thornlea, home to Harry and Carol Booth, from 1927.

The painting’s official title is not noted. The Thornlea painting is interchangeably referred to as Homeward Bound, Schooner on a Stormy Sea, Sailing Ship at Sea, and Marine. However, the 1901 Hopkin exhibition catalog does not list any paintings with those titles.

– Leslie Mio, Associate Registrar, Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research

If you would like to learn more about Robert Hopkin and the amazing club he inspired, join the Center for Edible Landscapes Dinner: An Evening at the Scarab Club in Detroit on Sunday, May 18th, 2025 from 5:00pm – 9:00pm.