In preparation for the Center’s upcoming seminar, featuring research on weaver Nelly Sethna, I became curious about an Academy of Art scholarship established in honor of Cranbrook founder, Ellen Scripps Booth.

Sethna had been a recipient of this financial award, which had allowed her to study abroad (Sethna was a citizen of India) at Cranbrook for one year, 1958-1959. Though it was Sethna’s artistic ability, not financial need, that earned her the award, she would never have made it to Cranbrook without this assistance, as indicated in letters to Weaving Department Head, Marianne Strengell.

Sethna’s subsequent successful career in textile design demonstrated the value of providing assistance for artists to attend the Academy. I wondered how many other similar stories there were in the Archives. I did not need to look past the first decade of memorial scholarship awardees to find plenty.

While the scholarship was granted to deserving artists in metalsmithing, painting, ceramics, and weaving in the ten years between 1951-1961, it was two fellow weavers of Sethna’s that caught my eye. They, too, had proven themselves worthy of distinction through their artistic accomplishments, but they, too, had financial needs that would have prohibited their attending the Academy otherwise.

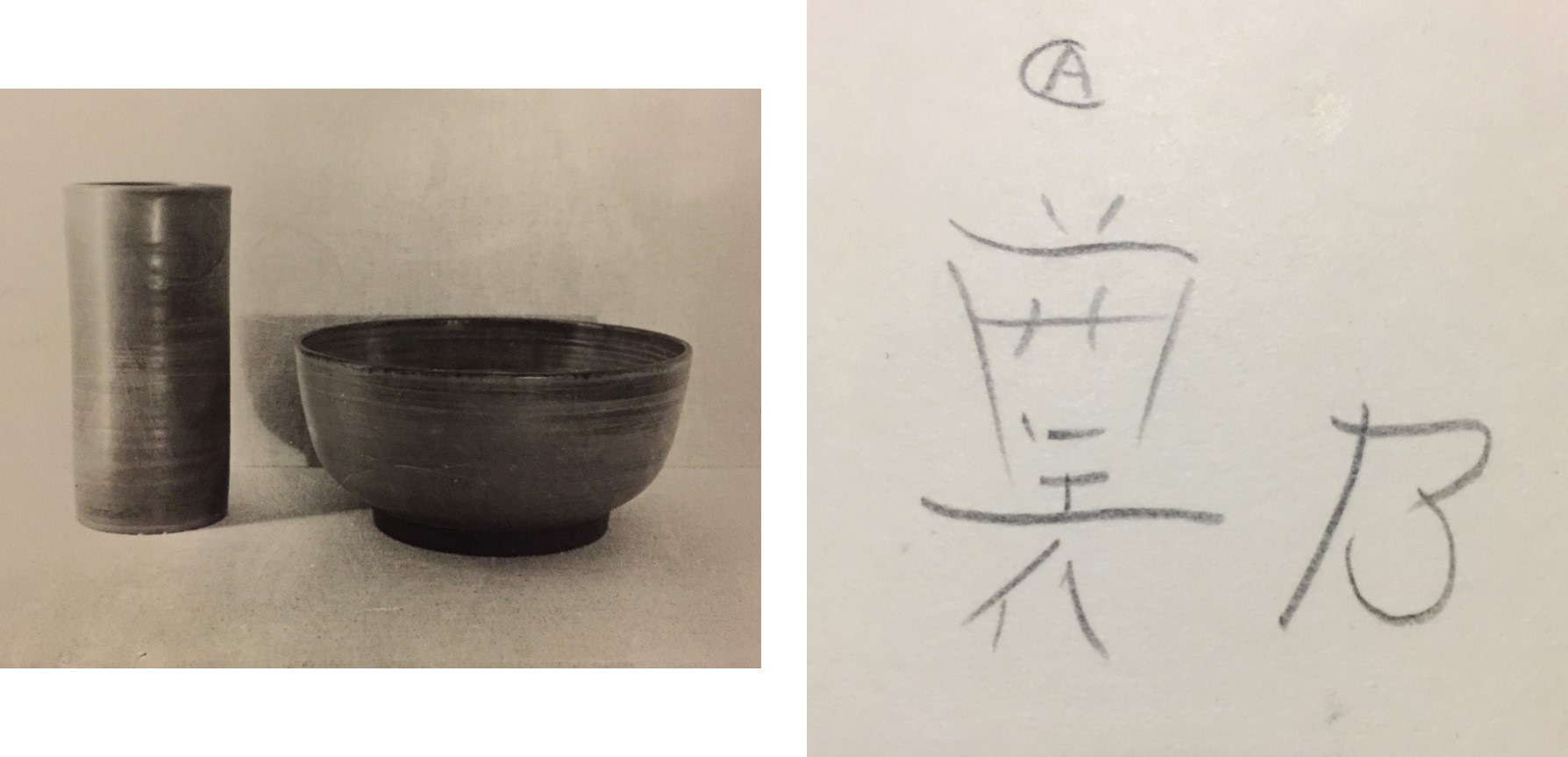

The first recipient of the scholarship was Katherine P. Choy, a Chinese expatriate and graduate of Mills College in Oakland, California. Choy came to Cranbrook in 1951 to study ceramics for one year as a non-degree student. She would spend near equal time in both the ceramics and weaving departments, under the dual tutelage of Maija Grotell and Marianne Strengell.

Upon leaving Cranbrook, she would enjoy success in both fields, first heading up the legendary Newcomb College Ceramics Department at Tulane University and later joining the design team at Isabel Scott Fabrics in New York. With fellow artist Henry Okamoto, Choy also founded The Clay Art Center in Port Chester, New York, which still exists today. Choy’s ceramics can be found in the collections of the Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, the Museum of Arts and Design in New York, as well as the New Orleans Museum of Art.

Another scholarship winner, and weaver, in the first decade of the award was Tsuneko Yokota (Fujimoto), for the academic year 1957-1958. A graduate of the Design Department at Tama College of Fine Arts in Tokyo, Yokota distinguished herself in fabric dying, winning several awards and a scholarship for an additional year at Tama as an honor graduate. At the suggestion of one of her instructors, and with a recommendation from Marianne Strengell, who knew her instructor, Yokota came to Cranbrook to further her studies in weaving and textile design. Unlike Sethna and Choy, though, Yokota stayed an additional year at the Academy and earned her MFA in Weaving.

By all accounts, Yokota lived up to Strengell’s confidence that she, “will most certainly have ample chance and desire to spread our particular brand of education and design in Japan,” working with celebrated modernist interior designers like Isamu Kenmochi.

The Ellen Scripps Booth Memorial Scholarship was established in 1951 along with the George Gough Booth and Eliel Saarinen Memorial Scholarships by the Academy of Art Board of Trustees. Academy faculty, under the leadership of Director Zoltan Sepeshy, recommended these scholarships be granted based on unusual merit of work submitted rather than financial need. Academy administrative documents indicate that the Ellen Scripps Booth Scholarship Fund had wide support from not only Academy faculty and staff, but also many at the Foundation, Press, Central Committee, and House. Scholarship award amounts varied somewhat from year to year, (in 1953 they were evenly split between two awardees), but the scholarship continued to be granted until at least 1965. While these named scholarships are no longer awarded (and I was unable to deduce exactly why or when they stopped), scholarships and financial aid for talented students are still vital to the success of the Academy and its artists.

—Deborah Rice, Head Archivist, Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research

Editor’s Notes: On Tuesday, June 22 the Center broadcasts live from Cranbrook and India for scholar Vishal Khandelwal’s examination, using materials from Cranbrook Archives, of a fascinating connection between mid-century textile design in the United States and India, as seen through the work of Nelly Sethna. Register here for this illuminating virtual event.

Along with Nelly Sethna (1958-59), find early scholarship winners, such as Paul R. Evans (1952-53) and Howard William Kottler (1956-57) featured in Cranbrook Art Musuem’s new exhibit and companion publication, With Eyes Opened. Find details and purchase advance tickets to the exhibit on the Museum’s website.

Read a recent exciting announcement about new scholarship and financial opportunities for students on the Academy’s website.