The Archives to Launch Our Poster Collection Online!

Over the coming summer, Cranbrook Archives will release a brand new collection into its online digital database! While building our digital archive is a perpetual process, we are working steadily to upload images and manuscripts so that you, our remote users, can browse and search through our collections no matter where you live. This summer we will be celebrating a new addition: the Cranbrook Poster Collection!

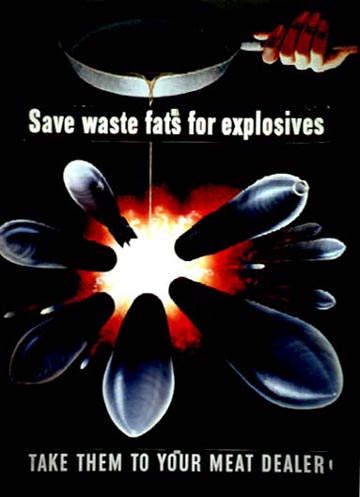

Over the past eight months, my colleague, Laura MacNewman, and I collaborated to upload this collection for online access. The posters date back to the early 1900s with topics covering the scope of the entire Cranbrook Educational Community, emphasizing exhibitions from the Academy of Art and the Institute of Science, and theatrical performances from Cranbrook Kingswood Schools, St. Dunstan’s Guild, and the Summer Theatre.

We created nineteen different series for the Poster Collection based on locations or departments on campus. We identified nearly 500 unique posters in our collection, and each one was given a distinct identifying number. Once the unique identifiers were established, we merged all the various poster inventories into one master inventory spreadsheet, and arranged them in chronological order by series.

The next step was sorting through the physical posters folder by folder in order to take a reference photograph of each one for the database, record their dimensions, and describe them in the master inventory spreadsheet. This was the longest stage of the process, lasting several weeks. After the data was entered into the spreadsheet, we renamed the individual images to match the posters’ unique identifiers in order to match the photograph.

While every step has been a learning process, my favorite part was working in Thornlea Studio and physically handling the poster collection for measurements and photographs. Laura and I were able to take a previously unorganized collection and make it discoverable online, which was rewarding and gave me a sense of accomplishment. I loved the huge diversity of the posters, too. Not only were they historically valuable, they were also aesthetically stunning. I can’t wait for the collection to be released for everyone to enjoy!

– Danae Dracht, Archives Assistant

Editor’s Note: Thank you Danae and Laura for your hard work on this project! Congratulations also to Danae who recently graduated from Wayne State University’s School of Library Science! We wish you all the best as you embark on the next journey of your archival career.