Each May, the Center is honored to host outstanding seniors from Cranbrook Kingswood Upper School for a three-week immersive internship.

This year two seniors, Kamilah Moore and Joel Kwiatkowski, worked with the Center and Archives staff, including writing blogs! Hear from Joel today and look out for Kamilah’s post next week.

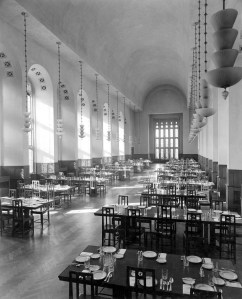

Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research is a name that invokes the image of some grand museum or hall, with many sterile prep rooms and rows upon rows of file cabinets. Now don’t get me wrong, there are plenty of file cabinets, but the Annex is far from grand. Instead, the rather humble staff apartment-turned-offices are befitting the lovely people there.

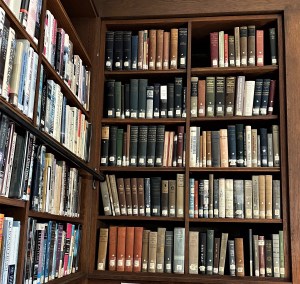

The Center’s Annex, next door to Cranbrook House, is situated above the House & Garden Auxiliary offices, up a set of winding stairs that require me to duck in a few places. But up there you will find a quaint little kitchen (complete with a toaster oven and healthy snack collection), a few offices, and closets and cabinets dotted with curiosities.

It was this atmosphere, over many chatty lunches, that I got to know Leslie Mio, the Associate Registrar, and Mariam Hale, the 2023-2025 Center Collections Fellow. It was a pleasure to find two individuals who cared so greatly for history and conservation, and we bonded over our shared love of museums and particular historical eras.

But, let it be known that work at the collections isn’t all comfortable work behind a desk or searching a filing cabinet. This illusion, if I ever had it, was quickly broken on my first full day of the internship. Our task? Moving five solid wood cabinets from the rooms of retirement-age nuns across the building to be used to store Cranbrook’s lacy dresses and costumes.

Briarbank, a neighboring estate to Booth’s land, was converted into a place for sisters to stay once they needed a bit more care later in life. But, at some point, the demand for a place such as that ran dry, and Cranbrook bought the campus. And now, in that spirit, I was near horizontal in my penny loafers, shoving a giant wardrobe into place across some very tasteful carpet.

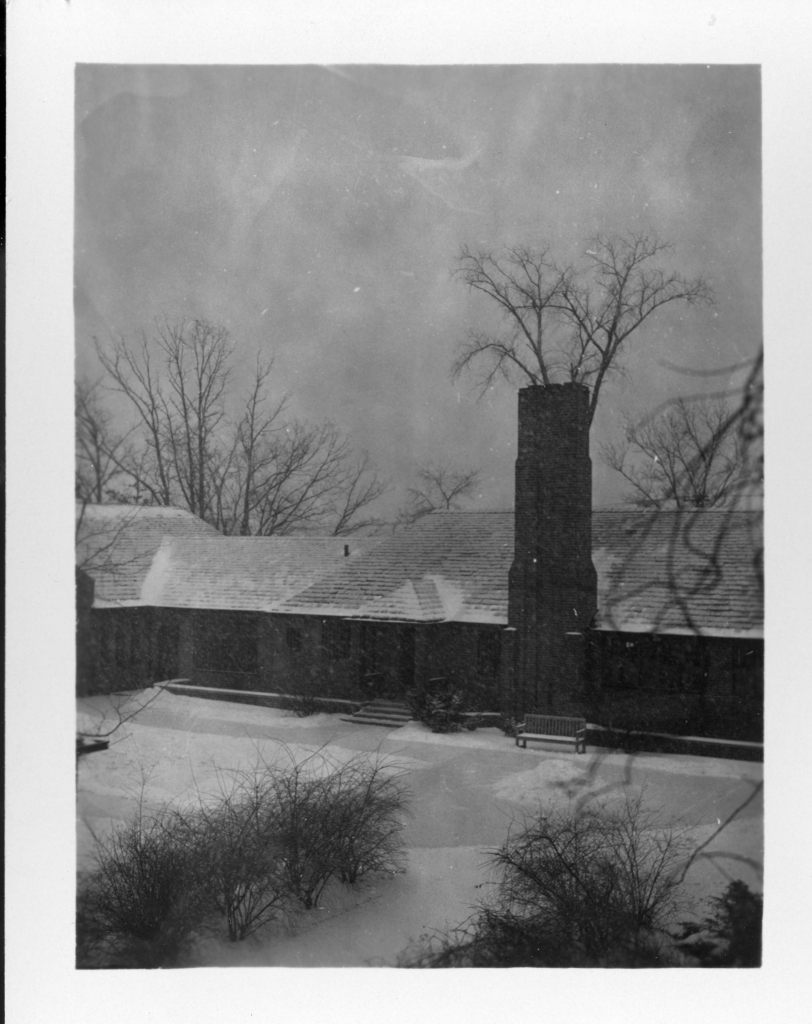

In the coming days, the purpose of these heavy cabinets would be realized, as we began the true overarching theme of my time at the Center: moving a seemingly infinite number of objects from the hot attic of Cranbrook House to the comparatively “less hot” and climate-controlled storage area at Briarbank. Paintings, prints, textiles, rugs, hats, and racks of clothing and costumes were deftly maneuvered through the halls and offices of Cranbrook House (or, alternatively, very carefully down the narrowest, steepest, stairwell known to mankind).

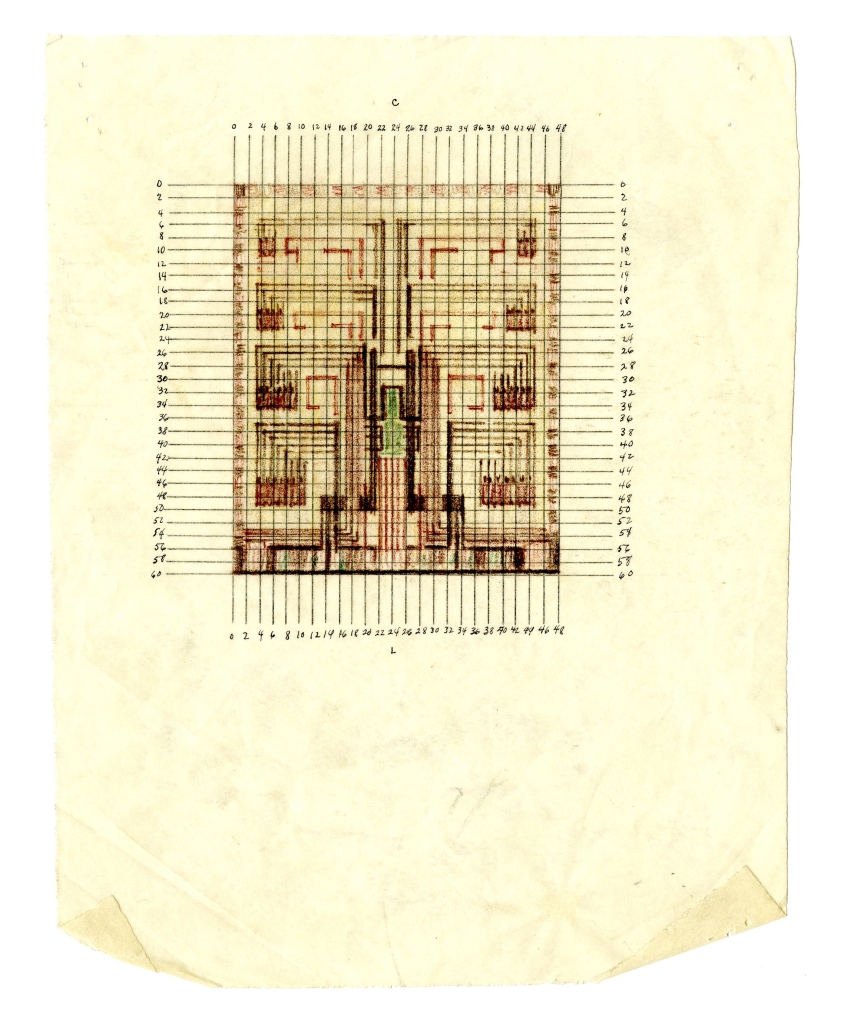

Each day packing and moving Cultural Properties in the attic was sure to bring new surprises. Everything from a fur hat belonging to George Booth to paper parasols, or entire handwoven rugs the size of a small house. While these days meant a bit of manual labor, they never ceased to bring me joy, as the wonderful folk of the Center doled out tidbits of Cranbrook’s story connected to each unearthed gem.

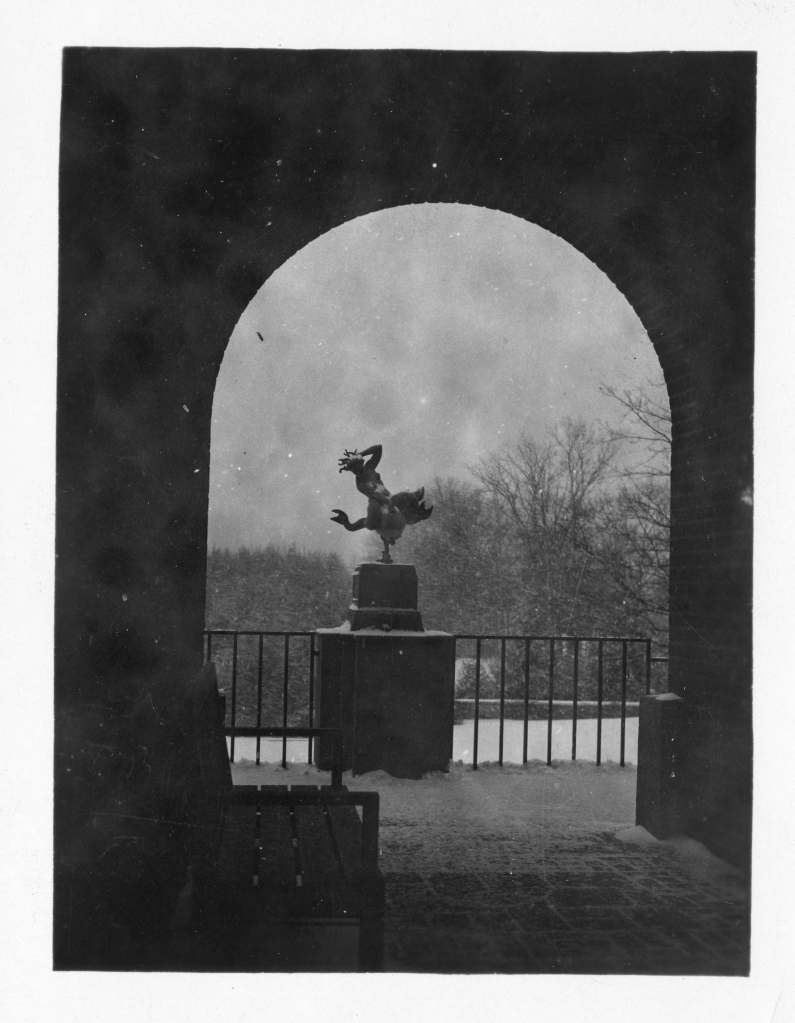

Now those familiar with the Center may be wondering: “Now wait just a minute. Where is my favorite curator? Where is the delightful presence of the steward of Saarinen House?” Well, fear not good reader, for while Kevin may not have been at every boxing and unboxing, Kevin joined Kamilah and me on many excursions outside the Samuel-Yellin-forged gates of Cranbrook. For those unacquainted, Kevin Adkisson is Curator of the Center, the veritable fountain of all knowledge concerning Cranbrook, and legend in his own time among students.

My first trip with Kevin came when we were tasked with heading to Detroit to give a tour of Holy Redeemer Church to a group of 8th graders from the Catholic school next door. I thought that getting middle schoolers excited about Corinthian columns would be impossible, but Kevin’s energy and skill made it look easy.

Afterword, we headed to visit the master ironworkers at Smith Shop, where the Eliel Saarinen-designed Kingswood main gate is being repaired and restored. I stood back and observed while Kevin, Cranbrook Capital Projects Director Jean-Claude Azar, and Amy Weiks and Gabriel Craig (co-owners of Smith Shop) debated the ins and outs of the gate’s making and breaking.

Across my three week Senior May, I also took trips to the paint store to debate shades of grey, the frame shop to mount an object, Ken Katz’s painting conservation studio, and even Birmingham’s historic cemetery. On each of these trips, I gained insight into the multifaceted work of the Center for Collections and Research, including care and handling, teaching, conservation, and cataloging.

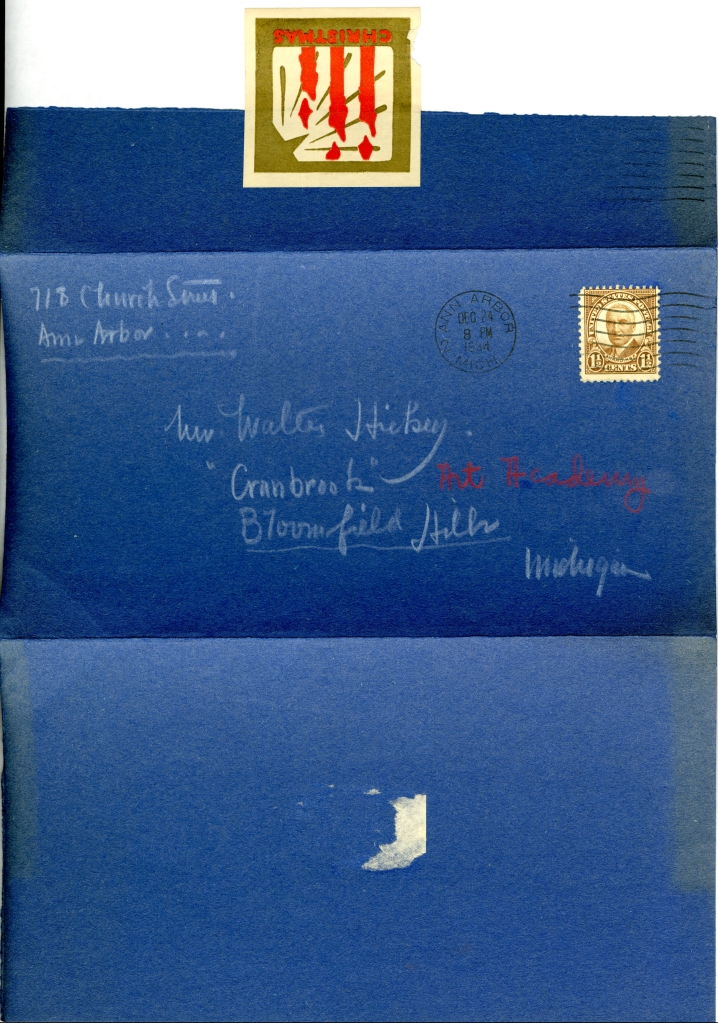

I cannot fully capture in a blog what a delight it was to be in the presence of such knowledgeable individuals. For every question about Cranbrook’s history, each member of staff was sure to add in their own expertise, citing obscure letters and photographs, adding a beautiful familiarity to their responses and giving color to the story of Cranbrook.

Of course, I would be remiss to leave out some of the other folks who make the Center function, like Greg, Jody, Amy, and Jess. These are the people who drive the work, managing, fundraising, and promoting the vision of Collections and ensuring the continued progress of the Center’s goals.

On my last day, I had the privilege of working with Jess Webster, Development Coordinator, who also helps run the Center’s social media. With Kamilah, I researched, drafted, workshopped, and delivered a script for an Instagram Reel commemorating the 150th birthday of Carl Milles., During my time working out ideas for the video (and even this blog), I gained a new appreciation for the way in which Cranbrook is viewed from the outside.

For me, as a student at Cranbrook, my view is that of someone on the inside, who has the privilege to walk by art on campus each and every day (admittedly at times without a second thought). But getting to see the behind-the-scenes of Cranbrook’s beautiful historic campus has given me an appreciation that feels wholly unique amongst my peers.

If you’ve read this blog, I urge you to take a moment to appreciate all that goes on caring for a 100-plus-year-old campus to live on to this day and serve its many students and visitors. From calls, texts, emails, and meetings, the Center is busy planning, filing, caring, and protecting the legacy of Cranbrook. The work is never done.

Yet despite the challenges, the Center rises to the task, willing to give their all to something they passionately care for. It would be hard not to be inspired.

This internship has truly been a dream-come-true, and I am grateful to Mariam, Leslie, and Kevin for their warm welcome and tutelage.

– Joel Kwiatkowski, Cranbrook Kingswood Upper School Class of 2025 and Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research 2025 Senior May

Editor’s Note: The Senior May Project is a school-sponsored activity that encourages Cranbrook Kingswood Upper School seniors to acquire work experience in a field they are considering as a college major, a potential profession, and/or as a personal interest.

Joel Kwiatkowski graduated from Cranbrook in June 2025 and will be attending the University of California San Diego in the fall to pursue a degree in Molecular and Cellular Biology. Joel first came to Cranbrook Schools in sixth grade, and has since gained a passion for the institution’s rich history of influential artists and personalities.