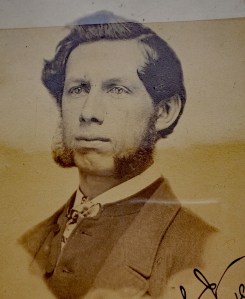

September 24 is the birthday of Cranbrook’s co-founder George Gough Booth. Trying to decide how best to commemorate his 157th birthday, I landed on the idea of sharing the story of the day he came into the world.

In 1864, Henry Wood Booth and Clara Louise Irene Gagnier Booth were living in Canada. Clara had already given birth to three children: Charles, Alice, and Grace. Baby Grace had, unfortunately, died at seven months. Clara would go on to have six more children—Edmund, Theodora, Adelaide, Ralph, Roland, and Bertha—for a total of nine children to live past infancy.

George Gough Booth arrived on September 24, 1864, at 8 Magill (now McGill) Street in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Henry Wood Booth recalled that George was, “Born in the house at the East end of row on the South side of Magill St. about the middle of the block from Younge St. at 11.30 p.m. on Saturday, Sept. 24, 1864.”

In a missive written much later about the night of George’s birth, Henry recalled “the time when, on opening the front door, I heard your sonorous voice for the first time, while your grandmother, coming down the stairs, assured me ‘it’s a fine boy.’”

But why was Henry out so late on the night George was born? Shouldn’t he have been home with Clara?

Distraught during Clara’s labor—”The warning came at about 10 p.m.” Henry recalled—the father-to-be was ushered out of the house to get help. His first stop was the home of Mrs. Cavie, across Magill Street, “who was in bed but promised to ‘dress and go over at once,’ which she did.” Henry then ran to Mother Gagnier’s house. She lived a mile away. “She also promised to go at once, and did.”

His final stop was the home of Dr. James Ross, who lived almost three miles away. Dr. Ross, however, took his time, dressing while a nervous Henry waited. He regretted waiting for the doctor, “I should have hurried home and told them there that the doctor was coming.”

George, “being a lively one,” commented Henry, “and his mother equal to the task,” had already made his entrance into the world, with the assistance of the experienced Grandmother Gagnier, before the doctor and Henry had reached the house.

George Gough got his first name from his great-grandfather as well as his uncle, both named George Booth. Gough came from two sources. Henry’s grandmother Elizabeth Dann Gough Booth had been a member of the influential Gough family back in England, and Henry’s father’s name was Henry Gough Booth.

In addition, Henry and Clara enjoyed the work of the famous temperance orator John Gough. Henry had once heard Gough lecture in 1849, where Henry signed “the pledge” to stop drinking, and became a champion of temperance. The Booths sought to dedicate George to “the sacred cause of temperance” and thought the strong middle name would help.

George Gough Booth did maintain a temperate life, so Henry and Clara’s goal was achieved.

Another thing Henry and Clara passed on to their son George: a tradition of honoring the family ancestry through names:

- George’s second son’s name was Warren, his wife Ellen Scripps Booth’s middle name

- His first daughter was named Grace Ellen, after his sister who died in infancy and his wife

- His youngest son was named Henry after his father, grandfather, and a long line of Henrys before him

- His youngest daughter Florence’s middle name was Louise, his mother’s middle name

- All three of his sons’ middle names were Scripps, his wife’s maiden name

And George and Ellen’s home, estate, and community they founded was, of course, named for the town in Kent, England, where Henry Wood Booth was born: Cranbrook.

And with that, I’d like to wish a very Happy Birthday, Mr. Booth!

—Leslie S. Mio, Associate Registrar, Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research

Continue reading