Light, temperature, and humidity can all harm a museum’s objects and artifacts. In a previous blog, I talked about what damage light can do and how we are combating that at the Frank Lloyd Wright Smith House. The battle for consistent temperature and humidity in the house is another issue.

In October 2018, we had a Conservation Assessment done at Smith House by ICA – Art Conservation. According to ICA,

Temperature can affect a collection in . . . significant ways. Elevated temperatures have the capacity to increase the rate of deterioration . . . [and] temperature affects relative humidity.

Relative humidity is the ratio of the amount of water vapor in a particular volume of air relative to the maximum amount of water vapor this same volume of air can hold at the same temperature.

As relative humidity fluctuates, the environment and the materials within it will seek equilibrium with one another . . . Within a museum or historic structure, the collection objects and building materials will act like a sponge to these fluctuations, which can cause irreversible mechanical damage.

In the museum community, it is recommended that the relative humidity be kept as stable as possible and the temperature as low as practicable. A relative humidity (RH) range between 55% to 35% is thought to be best for general conditions. However, it is the stability of the relative humidity that is more significant than the actual value. Temperatures below 72˚F and above 32˚F are considered acceptable when the relative humidity is controlled.

So, what was the Center to do? Equipment for monitoring (data loggers) was purchased. We started regular environmental monitoring throughout Smith House. Logs were created to record the environment ranges for temperature and relative humidity for the spaces.

Data loggers are devices equipped with sensors and a microprocessor to monitor and record data such as temperature and relative humidity. We chose Lascar’s EL-USB-2. This standalone data logger measures more than 16,000 readings and features a USB drive so data can be downloaded directly to a computer.

However, it is not always practical to carry a laptop around Smith House to download the data or remove the data loggers to download on my office PC. Instead, I use the EL-DataPad. It allows the configuration and download of temperature and humidity data loggers on the spot.

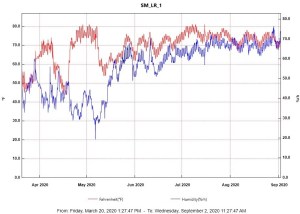

In the Smith House, the temperature and humidity is recorded every 30 minutes. I log this data and graph it, to see trends or issues in the house.

How will this documentation help conservation of objects in Smith House? The data will be useful for establishing achievable set points and ranges for the house environment. It will also be helpful for writing grants to help fund equipment or materials for further environmental management.

– Leslie S. Mio, Associate Registrar, Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research