Today, the Archives is pleased to announce the completion of a photographic negative rehousing project funded by the Fred A. and Barbara M. Erb Family Foundation. The first part of this grant-funded project ran from March 2017 through February 2018, when thousands of negatives were rehoused by Veronica Wood and Kaitlin Sharra Eraqi. The success of this first part allowed us to extend the grant project, and from November 2018 through June 2019 Veronica rehoused many more negatives. We are grateful to Veronica for her many hours of hard work and, as of today, over 20,000 Cranbrook School negatives have been rehoused.

Alongside this effort, we are thankful for the work of our steadfast volunteers—Lois Harsh, Judy Pardonnet, and Ellen Vanderkolk—who have been rehousing other collections. These have included the Portrait series, the Institute of Science series by Harvey Croze, Kingswood School, St, Dunstan’s Theater, the Summer Theater, the Cranbrook Community/Foundation negatives, and the Pleasures of Life. We also currently have two new volunteers, Aya and Brandon, who have completed rehousing of some smaller collections, including Marianne Strengell, Swanson Associates, and Carol Waldeck.

Why all of this rehousing? Many of the photographic negatives are made of acetate cellulose or nitrate cellulose, both of which have a plastic base which deteriorates over time. Cranbrook employed a professional photographer from 1933 to 1970, and their images were maintained by the Cranbrook Press Office before they were transferred to Cranbrook Archives. Here, they have been stored in their original plain paper envelopes or, more detrimentally, in plastic sleeves. As they age, we must stabilize the negatives for future generations by rehousing them in acid-free paper envelopes.

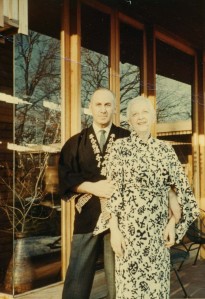

Mr. and Mrs. Price at the Cranbrook School Store, April 1963. Photographer, Harvey Croze, neg.CR3182-2. Copyright Cranbrook Archives.

The twofold goal of any archive is preservation and access of its holdings, and to this effect, much is achieved through arrangement and description—how the materials are stored, in what order, and how they are described. While the primary goal of the rehousing project was to address the physical preservation needs of our photographic negatives, it has also been advantageous for their intellectual control. As we work through thousands of negatives, photographs have been found alongside their negatives, as well as ephemera such as Summer Theatre playbills. These discoveries have helped us to enhance the descriptive metadata (the who, what, when and where) for the negatives. More detailed descriptions will help us, and our researchers, know what exactly is available within Cranbrook Archives.

The numbering system for Cranbrook photographs was developed by Richard G. Askew, Cranbrook photographer from 1933-1941. There were several short-term photographers until Harvey Croze became the photographer from 1943-1970. Each collection has its own index, which records the negative number given to each photograph, the content of the photograph, when it was taken, and by whom. However, sometimes the content field may only record an event without giving any details of who is in the photograph.

An unexpected outcome of the Erb Foundation negative rehousing project has been to enhance the metadata in the indexes, whether by seeing the photographs with the negatives and being able to identify the people or places, or by cross-referencing with the collections to establish the context of the content. By adding in more information to the metadata in this way, the usefulness of the negative collection is improved and the relationships between collections are also strengthened. I would like to share with you some examples of these discoveries that will help us to know more about the people, places, and things of Cranbrook.

The following are examples of images that were recorded by only their event name. Now, the index contains the names of the individuals and objects, enabling us to better utilize the negatives:

Henry Scripps Booth photographed during an Editors visit to Cranbrook, 1958. Photographer, Harvey Croze, neg. FD84-22. Copyright Cranbrook Archives.

“Formal Garden Opening” 1951. Unknown (Roman Warrior) by Unknown (Italian).

Bequest of George Gough Booth and Ellen Scripps Booth to the Cranbrook Foundation. Photographer, Harvey Croze, neg. CC201. Copyright Cranbrook Archives.

As another example, before our negative rehousing project, a researcher looking into Lillian Holm would have been highly unlikely to discover this picture of her. The image was previously indexed only as “Founders’ Day 1965”:

Henry Scripps Booth, Josephine Hodges Waldo, Lillian Holm and Carl G. Wonnberger on Founders’ Day 1965. Photographer, Harvey Croze, neg. FD244-85. Copyright Cranbrook Archives.

Another interesting find was a series of photographs for which the index simply noted “Jack Speohr, Cranbrook School alumnus.” Wanting to know more, I looked up Speohr in the Cranbrook Institute of Science newsletter index. I learned Jack Spoehr, who graduated from Cranbrook School in 1949, and went on to study ethnological studies at Harvard. In 1950, he visited a remote part of Mexico called Cuauhtémoc, which about 75 miles southwest of Chihuahua City, where he studied the native peoples there, the Darámuli, (also called Tarahumara), who often crafted violins both for trade and for use in religious ceremonies. A short article, ‘A Visit to the Tarahumaras,’ about his observations there, is published in the Cranbrook Institute of Science Newsletter, Vol. 21 No.1, of September 1951. The first photograph, below, shows a member of the Darámuli just as Spoehr describes on page 3 of his article.

A member of the Darámuli (Tarahumaras). Photographer, Jack Spoehr, neg. CC277-9. Courtesy Cranbrook Archives.

A member of the Darámuli (Tarahumaras) crafting a violin. Photographer, Jack Spoehr, neg. CC277-13. Courtesy Cranbrook Archives.

For those who have not been delighted by the weather recently, you will see that it was much worse in June of 1969, when there were floods at Brookside and Kingswood:

View of the old Meeting House during flooding at Brookside, June 1969. Photographer, Harvey Croze, neg. FD290-12. Copyright Cranbrook Archives.

View of the Japanese Garden bridge during flooding at Kingswood, June 1969. Photographer, Harvey Croze, neg. FD290-12. Copyright Cranbrook Archives.

Filed among the negatives, we have found numerous playbills from both the Summer Theatre series and the Ergasterion performances in the Cranbrook School series. These relate to their respective manuscript collections as well as the poster collection, which was completely digitized in 2015. It is interesting to see Sara Smith as Director of some of the plays as the Smith House Records are currently being processed and will be open for research later this year.

The playbill for the Summer Theatre performance of Seven Sisters, 1950. Copyright Cranbrook Archives.

Seven Sisters Dress Rehearsal, 1950. Photographer, Harvey Croze, neg. #ST218-3. Copyright Cranbrook Archives.

We are very pleased to have made these new connections across existing collections within Cranbrook Archives, and are grateful to the Erb Family Foundation for enabling us to better preserve these important images.

– Laura MacNewman, Associate Archivist