Marthe Julia LeLoupp, born October 10, 1898, in Plogoff, Finistere, France, was an original faculty member of Kingswood School, where she taught French from 1930-1956. Having completed the Diplȏme de fin d’études at the Lysée Brizeaux, Quimper, Finistere, France in 1917, LeLoupp then completed her BA at Macalester College, St. Paul, Minnesota in 1920. She later completed graduate work at the University of Chicago (1929-1931) where she worked on an MA Thesis: Influence du Breton sur le français régional en Bretagne. With teaching experience in schools and colleges in Minnesota, South Dakota, New York, New Jersey, and Indiana, LeLoupp arrived at Cranbrook in 1930.

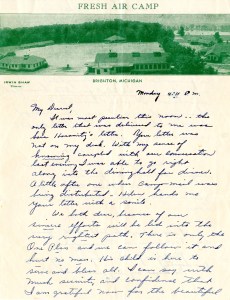

Correspondence with LeLoupp in the Kingswood School Records is limited but suggests that she would return to France each summer. A letter from LeLoupp, written in Paris on September 17, 1939, tells how she left America in June with ticket safely tucked in her purse for a return September 6th on the Normandie. But, the declaration of war had made this impossible and her ticket had been passed, initially to the DeGrasse to sail on the 13th and then to the Shawnee, due to depart Bordeaux on the 22nd. The Shawnee, she explains, had been, “sent to the rescue of a few hundred thousand American citizens, who are anxiously waiting for transportation westward.” On arriving to Bordeaux on September 22, 1939, Le Loupp writes that they were told, to their great dismay, that the Shawnee would not sail until the 26th. While LeLoupp’s letters were on their way to Cranbrook, Ms. Augur [Kingswood School Headmistress, 1934-1950] was searching for LeLoupp, first sending a telegram and then consulting the American Consul. LeLoupp’s mother returns Ms. Augur’s telegram with a letter explaining her daughter’s situation. Discovering this story recently, I wondered at the extraordinary resonance with current concerns for travelers, and for those unable to complete their journeys.

Despite the harrowing circumstances, LeLoupp did eventually make it across the Atlantic. She continued to teach French at Kingswood School until July 1956, when she writes from Bénodet in France to request to be released from her 1956-57 contract due to poor health, ending the letter, “I find it impossible to express my regret in words.” Not much else is known about LeLoupp’s time at Cranbrook, except that she lived for twelve of her years at Cranbrook in the apartments above Kingswood School, which were converted in 1945 from the ballroom known as Heaven. In the KBC [Kingswood Brookside Cranbrook] Quarterly of May 1973, LeLoupp was remembered thus,

“a “beautiful person” with a “super smile”. She was “sweet and kind” and always beautifully dressed in classic tweeds. Peering over her bi-focals at her students and reciting in her strong French accent the terrible weekly dictes that no one could understand, she was one of those who inspired her girls to excellence or accomplishment in French that is still one of Kingswood’s greatest assets”.

Laura MacNewman — Associate Archivist